Whiteness and the Working Class

A conversation with Noel Ignatiev and James Murray

In light of the recent wave of anti-immigration protests and riots in the British Isles, I am publishing an interview that I conducted over six years ago with Noel Ignatiev and James Murray. This interview was originally published on January 18, 2018 at Orchestrated Pulse, a now defunct outlet to which I contributed a number of pieces in the 2010s.

Ignatiev (who passed away in 2019) is a controversial figure on both the left and the right. His emphasis on the central role of “whiteness” in undermining the success of working class politics in the United States has been met with resistance from many Marxists (who view him as exagerating the significance of race in relation to class struggle) as well as from many conservatives (who believe that his call for whites to abandon their racial identity constitutes racism against white people).

Ignatiev’s 1995 book, How the Irish Became White, addresses the racial transformation of the Irish who migrated from Ireland to the United States. While his book is primiarly about the American context, recent images from an anti-immigration rally in Belfast showing the Tricolor and Union Jack hoisted side by side also raise important questions about the relationship between Irish and white identity in contemporary (Northern) Ireland. Whatever you think about Ignatiev’s ideological disposition, the issues he brings up are undoubedtly salient. Though some of my own views on these topics have changed over the past six years, I still find this interview very relevant to today’s world.

James Murray, the radical son of an Oklahoma steel worker, joins Ignatiev for the interview. Murray and Ignatiev discuss how they got into politics, the historical significance of the Civil War, the meanig of “white privilege,” the pitfalls of antifa, and what gives them hope for the future. I hope you enjoy it. Without further ado, here is the interview. -Vincent

January 18, 2018

I had the pleasure of sitting down with two editors from Hard Crackers, Noel Ignatiev and James Murray. Hard Crackers is a periodical founded in 2016 that deals with race from a perspective that has deeply informed my own. It grew out of discussions among people who had been involved with Race Traitor, a journal that ran from 1993 to 2005 and, as Noel notes in our interview, “was the only publication we knew of whose writers and readers ranged from university faculty members to prison inmates.”

Vincent Kelley: One of the things we try and do at Orchestrated Pulse is connect personal stories to a materialist politics. Noel and James, could you both talk a bit about the life and political experiences that gave birth to projects like Race Traitor and Hard Crackers?

Noel Ignatiev: After sixty years of political activism and study I can boil down what I have learned into three propositions: 1) Labor in the white skin cannot be free where in the black it is branded; 2) for revolutionaries, dual power is the key to strategy; 3) The emancipation of the working class is the task of the workers themselves.

VK: What exactly do you mean when you say “dual power is the key to strategy”?

NI: No revolution has ever taken place without passing through a phase of dual power; people overturn an existing society and create a new one only when the new society has appeared in tangible form—workers’ councils, liberated zones, etc. The task of revolutionaries is not to wait until these new forms are fully matured before transferring their loyalty to them but to recognize them in their embryonic stages, elaborate them, link them together, pose them against existing patterns and help those who invented them become conscious of their implications. That is what I mean by a strategy of dual power.

VK: What drove you to undertake all these years of political activism and study in the first place?

NI: I couldn’t say why I chose to devote my life to communism. My parents, and on my mother’s side my grandparents, were Communist Party USA members; but my brother and sister grew up in the same home I did under similar conditions and have chosen to follow another course. I can only regard myself as the product of an accidental coming together of molecules and vectors; the only certainty is that there will always be accidents.

VK: Besides this family background, could you talk a bit about those who have given you inspiration and sustenance on your political journey?

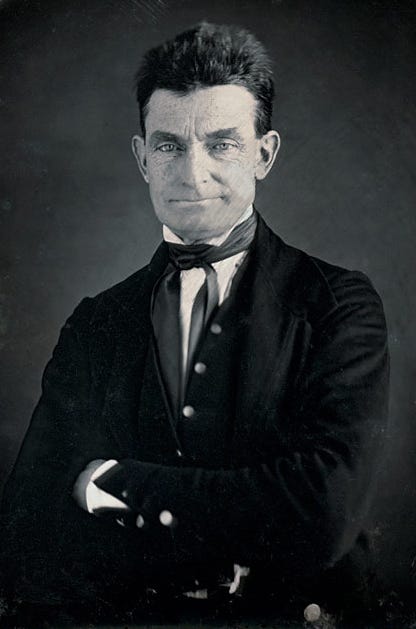

NI: I am inspired by artists who have imagined the possibility of people being more than they are, and by those moments in history and individuals I have known who have embodied that possibility. I mention three heroes: Abby Kelly, who on leaving her infant daughter with her sister so she could travel and organize for the antislavery cause, said that nothing in her life ever gave her so much pain but that she did it for the mothers whose babies were sold away from them. The second is Malcolm X, who showed how a person can transform himself. The third is John Brown, who came closest of any European-American to escaping the bounds of whiteness.

VK: What about you, James?

James Murray: My dad was a steel worker and an off and on United Steelworkers delegate, so I grew up going to union picnics, watching strikes, etc. Some of the strikes got pretty intense—property destruction, drive by shootings, all that. So as a natural rebel I never had any interest in unionism. And in the end all that drama accomplished nothing. My dad and all those guys were jobless by their late 50s, in broken health, no pensions, the steel mills closed down.

I got into ‘the anarchy thing’ via punk rock as most people my age did. I encountered a ‘proto Race Traitor theory’ in the Weather Underground book Prairie Fire, but even as a rube I could tell the book was kooky to say the least. I remember perfectly when I saw the Race Traitor book in a Barnes & Noble and was instantly intrigued. After reading it I was convinced and have been preaching the gospel ever since. This was the era of the ascendance of ‘gangsta rap’ and I was totally into it. Race Traitor seemed to jive with all that, at least in my imagination, and Ice-T, NWA, etc. seemed accepting of whiteboys if they were anti-authoritarian, contrary to the police. So I saw there were both ‘intellectual’ and ‘street’ currents I could identify with. Both of these currents, of course, rejected liberalism and I always hated anything remotely liberal.

VK: Noel, how do the three propositions you mentioned earlier tie into founding Race Traitor and Hard Crackers?

NI: Both Race Traitor and Hard Crackers embody these propositions, by seeking to discover and document the efforts of ordinary people to overturn the mess we are in.

VK: Why did you choose a popular song sung by Union soldiers as the name for the publication?

NI: The song “Hard Crackers” was an adaptation of “Hard Times,” perhaps Stephen Foster’s loveliest tune. Union soldiers sang it, with its lyric “Come again no more,” as a comment on what they were fed. We wanted to honor and identify with both their attitude and their carrying out one of the greatest revolutions in history.

VK: That’s interesting you call it that. Most on the left, including the American left, don’t include the Civil War and Reconstruction in their list of “the greatest revolutions in history.” Why is it so important that we do?

NI: The more I study the Civil War and Reconstruction, the more I am confirmed in the belief, derived from Du Bois, that together they represent a revolutionary upheaval as great as any. Not the English Revolution of the seventeenth century nor the French of the eighteenth involved such great masses of people nor such tremendous armies as the American Civil War; neither the Russian nor the Spanish Revolutions of the twentieth century took people from such a low state and hurled them so close to power as did the revolution that took “property” and turned it overnight into soldiers, citizens, voters and officeholders. Only the Haitian Revolution of the eighteenth century and the Chinese of the twentieth compare with the American experience in breadth and depth, and in neither of those cases did the downtrodden come as close to power for as long as did American slaves after the Civil War. Consider these words from Lincoln’s Second Inaugural Address:

Fondly do we hope, fervently do we pray, that this mighty scourge of war may speedily pass away. Yet, if God wills that it continue until all the wealth piled by the bondsman’s two hundred and fifty years of unrequited toil shall be sunk, and until every drop of blood drawn with the lash shall be paid by another drawn with the sword, as was said three thousand years ago, so still it must be said “the judgments of the Lord are true and righteous altogether.”

Never have more revolutionary sentiments been expressed. The person who spoke those words was not the same person who took office four years earlier determined to preserve the Union at any cost; the Revolution made him. Moreover, the Civil War and Reconstruction, while it did not fulfill all the hopes of its most radical partisans, did not disgrace itself by the actions of its leaders as did so many of the revolutions of the next century. As Du Bois explained, “It is only the blindspot in the eyes of America, and its historians, that can overlook and misread so clean and encouraging a chapter of human struggle and human uplift.”

JM: I think it’s strange that American radicals will often know minutia about Russia in 1917 or Spain in 1936 and almost nothing about the American Civil War. Why this is I don’t know—this country is a long way from Spain or Russia, the U.S. is a very artificial creation. And in my conjecture—on a continent with more small arms than people—revolution and civil war would be indistinguishable.

NI: James, not every civil war is a revolution, but every revolution is a civil war, don’t you think?

JM: Probably, but that’s not the popular conception of revolution as it exists among radicals today. They tend to think of “general strike,” or even, sadly, electoral politics. Of course I’m a southerner, so that prejudices my view—but I see 0 percent chance of a nonviolent end to white supremacy.

NI: This reminds me of what John Brown wrote on the note he handed to the guard before his death at the gallows in 1859: “I, John Brown, am now quite certain that the crimes of this guilty land can never be purged away but with blood. I had, as I now think, vainly flattered myself that without very much bloodshed, it might be done.”

VK: Let’s connect this to the contemporary context. Noel, in an introduction to Hard Crackers at Counterpunch, you mention that the Hard Crackers editorial board is comprised predominately of “white boys.” At the same time, one controversial piece on the site’s blog explicitly criticizes Redneck Revolt—a group that says it draws inspiration from John Brown himself—on the grounds that, “white people organized as whites are dangerous to the working class and to humanity, and white people with guns organized as whites are doubly so—and this is true regardless of the intentions of the organizers.”

From this contrast, it is clear that, despite being white, you don’t see yourselves as “white people organized as whites.” In a political climate of liberal anti-racism and multiculturalism that is suspicious of this kind of non-representational distinction, how and why do you think this is important to make?

NI: We started with people conventionally classified as “white”; we didn’t view that as a virtue, and, unlike some others, did not accept that definition of ourselves; we simply decided to begin with what we had and do the best we could. If our work is successful it will perhaps change the composition of our editorial board and, more important, help break down socially imposed definitions of “race.”

VK: Upon coming back to my hometown after several years spent mostly away, I found out that a former acquaintance is now known as a thug around town. He prides himself on beating up fascists, but a friend said he robs and beats up others too and has a very similar personal aesthetic to these fascists themselves.

I’ve written a critique of this “antifa” tendency here at Orchestrated Pulse, that borrowed heavily from your own over at Race Traitor from over 20 years ago. Could you talk about why antifa activity can often seem so similar to that of its declared antagonist?

JM: I’ve seen the exact same thing. Antifa and the fascists are in a symbiotic relationship; they are the only ones who take each other seriously. After the brawl, as always, the police restore order and everyone goes out for beers. The biggest problem with antifa, as I see it, is that they cannot understand—or don’t want to understand—that organized fascism has no power and is responsible for a miniscule amount of violence toward non-whites. The police are, of course, responsible for much violence, and have considerable political clout. But there would be significant penalties for fighting the police, so antifa doesn’t go there.

NI: I go along with James—although I might say what he said more gently with the hope of winning over some of the antifa as well as some of those influenced by fascists.

VK: Antifa specifically targets “racists,” but, Noel, you argued in 1997 that, “Just as the capitalist system is not a capitalist plot, so racial oppression is not the work of ‘racists.’ It is maintained by the principal institutions of society…” Could you elaborate on this and tie it in with the current debate?

NI: Well, to many, “racism” and “racists” are more accessible targets than the institutions that reproduce race, such as the schools (which define “excellence”), the labor market (which defines “employment”), the criminal justice system (which defines “crime”), the welfare system (which defines “poverty”), the department of children and family services (which defines “family”)—all run by people who would be sincerely horrified to be called “racists.”

Thirty thousand people marched in Boston following Charlottesville, carrying banners denouncing “racism” and even white supremacy but saying nothing about the reality in Boston, which is one of the most segregated cities in the country. The police provided protection, the mayor and leading politicians spoke at the rally, and afterwards the marchers returned to their normal lives feeling good about having taken a stand against “racism.”

VK: In the wake of Trump’s electoral victory, there has been much discussion of the “white working class” in both mainstream and left media, with some using the term liberally and others condemning it as “nothing but a racist dog whistle.” What is your take on the term and its utility or lack thereof?

NI: There is no such thing as the “white working class,” although there are white workers or, if you prefer, working-class whites. To accept the existence of a “white” working class is to embrace the heart of ruling-class ideology, which elevates local and partial interests above the interests of a class that seeks to bring to birth a new world from the ashes of the old.

VK: On a related note, let’s talk about the term “white privilege.” Can you trace a history of the term and how it has changed since the days of Race Traitor? Do you find it to be as useful a concept as it was in the 1990s, or has it been, as has been argued before at Orchestrated Pulse, irredeemably co-opted by the anti-racism industry?

NI: John Garvey and I began Race Traitor with the goal of breaking up the white race, as a contribution to working-class solidarity. We never used, endorsed or promoted identity politics; we railed against multiculturalism and “diversity”; we were scornful of those who wanted to preserve the “good aspects” of “white culture” or to “re-articulate” or “decenter” whiteness. We wanted nothing to do with the growing academic field of “whiteness studies.” We did share some vocabulary with individuals and organizations that were traveling on different roads to different places.

The most significant instance of this was the word “privilege.” In light of the political travesties that have developed under the term since, we wish we had differentiated ourselves more categorically from those who wanted to make careers in journalism, social work, organizational development, education and the arts, and who insist that the psychic battle against privilege must be never-ending; instead of challenging institutions they scrutinize every inter-personal encounter between black people and whites to unearth underlying “racist” attitudes and guide people in “unlearning” them. Hectoring people about their privileges was never our approach; it is an annoyance rather than a challenge.

VK: If we are not to hector people about their privileges, but still need to challenge white privilege, as described in Race Traitor as “a strategy for securing to some an advantage in a competitive society,” what can be our starting point? My question relates to yet another road, traveled most notably by someone like Adolph Reed, which seeks to identify common interests among working class whites and blacks and challenge racism by emphasizing and building upon those interests. I would guess that this is not your approach, which would likely advocate a more direct reckoning with whiteness, including the ways in which it undermines the potential for solidarity in the first place. If so, how can organizers start doing this?

NI: Adolph Reed can speak for himself; I take as my starting point the words of C.L.R. James, “Every white worker, whether he knows it or not, is being challenged by every Negro to take the steps which will enable the working people to fulfill their historic destiny of building a society free of the domination of one class or one race over another.” The aim is not to seek “common interests” based on present notions of “interests” but to hold fast to the conviction that “an injury to one is an injury to all”—in a different idiom, “Remember them that are in bonds as bound with them.”

Reform is the byproduct of revolutionary struggle, and progress is linked to bringing to life the vision of a society without race, gender and class, without commodity production and the buying and selling of labor-power, a society where “work” and “play” give way to freely associated activity. This I believe: solidarity that puts off equality until some time in the future is no solidarity at all; there will never be a successful proletarian revolution in this country until masses of white workers not merely oppose “racism” and “support the black struggle” but demonstrate that they are willing to go through what the black workers have gone through. It is my faith that the capacity to do so exists among them; central to the project of Race Traitor and Hard Crackers is to bring that capacity to life.

VK: That seems like a tall order, especially in light of the history you tell in your book, How the Irish Became White. Where do you find the most hope?

NI: In the conviction, widespread among the ordinary people of this country, that they can accomplish anything they will, and in their deeply ingrained tradition of lawlessness.

VK: And what can we do to activate that conviction and tradition in a way that, as Marx would have it, might not just interpret, but actually change the world?

NI: C.L.R. James says somewhere that in this world if you have an idea and get together with a few friends and publish your idea, you never know what will happen. As Margaret Mead is supposed to have said, those who despair of a small band of dedicated individuals changing the world should remember that nothing else ever has.

VK: Some friends at the Saturday Free School in Philadelphia have argued that universities have failed “to create knowledge for the people because of their deep ties to the neoliberal capitalist establishment” and, therefore, “see a need for spaces outside these institutions which can create knowledge that is scientific and tied to revolutionary practice.” Do you agree with this analysis? If so, how would publications like Race Traitor and Hard Crackers fit in?

JM: Yes, I agree. The dynamic you describe is apart from (or maybe not?) the ‘PC culture,’ speech codes, and so on that seem to dominate the university spaces nowadays—this is just my outsider view. I’ve been thinking for a while that critical theory would be driven underground, like the witch cult in the Middle Ages, and that this would happen not because of pressure from the right, who don’t even know critical theory exists, but rather from liberalism. Maybe publications like Hard Crackers are a response to this.

NI: The only thing I would add to what James said is what we used to say of Race Traitor—and we could say the same of Hard Crackers: it was the only publication we knew of whose writers and readers ranged from university faculty members to prison inmates—for the most part not the same people. Who knows, before we are done some of the university types may be in prison and some of the inmates may sit on university faculties.

JM: Noel’s comment explains why Race Traitor was the rarest type of literary journal—it changed people’s lives, and is still changing them. Liberalism, even wearing a cloak of radicality, never has that power.

Excellent interview. Thanks for sharing.