The Era When Nothing Ever Ends

Exploring the role and root of perpetual polycrisis

If you’ve ever taken a flight in the United States after 2006, you are aware of the ritual of removing your shoes at airport security. While this may seem odd to those who have never traveled in the United States, Americans have become habituated to this practice while flying in the country. 18 years after it was prescribed, the shoes-off ritual is less of a frustration than a compulsion. Passengers are now eager to remove their footwear as rapidly as possible when their spot in line approaches the security conveyor belt. It may be irritating, but most air travelers have recognized that efficiently complying is the best way to adapt to a rule that, while less than two decades old, has come to feel like an immutable law of nature.

The shoes-off rule was implemented by the Department of Homeland Security in 2006, apparently in response to a failed shoe bombing attempt back in 2001. Despite the fact that the threat of shoe bombings is hardly a regular news story in the United States, the rule has persisted. This rule is just one example of how an overreaction to one historical event can set into motion a new policy that soon appears impossible to reverse. While there has been much talk of phasing out the shoes-off rule (it has been relaxed for children and the elderly), no such universal rollback has occurred.

The Wall Street Journal recently published an article entitled “Israel’s War With Hamas Has No End in Sight.” Before reading the reporting, I had a sense of déjà vu. It felt like the geopolitical corollary to the no-shoes rule: Once a policy (or a war) begins, there’s a high probability that it will never end. What’s more, I felt like I didn’t even need to read beyond the subtitle to know what the general tenor of the article would be. “Existential stakes,” “ambitious goals,” and “long conflict” clearly communicated the fatalistic essence of what was to follow.

Sure enough, the article went on to establish a sense of inevitability to Israel’s continued assault on Gaza and the increasingly global conflict that it has provoked. The central question was not whether the war should continue, or how it could be brought to a close. Rather, the article sought to establish why it is irrational to think that it will ever end at all.

“The New Normal” and “No End in Sight”: Mantras of the 2020s Media Establishment

The Wall Street Journal’s language on Israel and Gaza is eerily similar to the narrative constructed around two other recent global crises: Covid and the Ukraine War. Before lockdowns were widespread in the United States, I recall receiving emails from academics already employing the now infamous phrase, “the new normal,” and expressing resignation to an indefinite global pandemic. This narrative was also widespread across mainstream media outlets. The message was clear: The pandemic may eventually end at an undetermined future point, but the new social and behavioral overhauls required to combat it will not.

For example, The New York Times reported in April 2020 that “Changes in how we think, behave and relate to one another — some deliberate but many made unconsciously, some temporary but others potentially permanent — are already coming to define our new normal.” NPR joined the chorus a week later with an article entitled, “New Normal: How Will Things Change In Post Pandemic World.”

This “new normal” narrative was highly effective. So effective that the world’s leading technology magazine, Wired, insisted less than a year ago that the pandemic itself was not yet over. Shortly after, the renowned Cleveland Clinic chimed in with an article headlined, “No, The Pandemic Isn’t Over.” Even for those who accept the end of the pandemic proper, The New York Times’ April 2020 declaration of a new normal in thinking, behavior, and relationships rings true.

The Ukraine War, like the pandemic, has been consistently described as an indefinite crisis. The BBC reported as early as April 2022 that “This is going to be a long, attritional struggle.” Just last month, American diplomat and current United Nations Under-Secretary-General for Political and Peacebuilding Affairs, Rosemary DiCarlo, stated that the Ukraine War has “no end in sight.”

The “new normal” and “no end in sight” narrative is notable for many reasons, not least because of its consistent disregard for facts. Lockdowns were justified based on incorrect modeling and were not the only pandemic response option. Likewise, the United States actively sabotaged a peace deal between Russia and Ukraine that could have ended the brutal war long ago.

There is similarly no law of nature stipulating that Israel’s genocidal siege on Gaza be indefinite, yet the media narrative—just like with covid and the Ukraine War—has led the public to believe that nothing can be done to end this crisis.

Why do we live in an era when nothing ever seems to end? To help answer this question, we must carefully consider the concept of crisis and its relationship to the media in the 2020s.

Manufacturing Polycrisis

In 1988, Edward S. Herman and Noam Chomsky published their famous critique of mainstream American media, entitled Manufacturing Consent: The Political Economy of the Mass Media. In it, they argued that

the powerful are able to fix the premises of discourse, to decide what the general populace is allowed to see, hear, and think about, and to ‘manage’ public opinion by regular propaganda campaigns.

This “propaganda model” relied heavily on the argument that the centralization of media corporations in the United States enabled their tight control of political narrative.

In the 2020s, the dominance of the centralized media giants has come under frontal assault from decentralized text and video platforms on the internet. As a result, Herman and Chomsky’s propaganda model no longer possesses the same explanatory power that it did when Manufacturing Consent was first published in 1988. Easy access to alternative viewpoints online has shattered Americans’ trust in the mainstream media. Consent can no longer be manufactured with the same reliability. This state of affairs presents serious problems for the forces that have relied on manufacturing consent as a key weapon in their arsenal to retain power and control.

This brings us back to the topic of crisis. Deprived of its ability to consistently manufacture consent, the 2020s ruling class—defined more than ever before by big tech and high finance—now seeks to manufacture crisis in order to maintain its grip on power. In particular, the “Terrible Twenties” have been witness to the manufacture of what

has called “polycrisis,” which he defines as follows in a widely-circulated Financial Times opinion piece:A problem becomes a crisis when it challenges our ability to cope and thus threatens our identity. In the polycrisis the shocks are disparate, but they interact so that the whole is even more overwhelming than the sum of the parts. At times one feels as if one is losing one’s sense of reality.

The major crises of the 2020s—including but not limited the covid pandemic, Ukraine War, and conflict in the Middle East—have not occurred as separate, sequential events, but, rather, have converged and compounded upon one another to produce a state of “polycrisis.” This polycrisis throws the stability of the status quo into question due to both the scale and interlocking nature of the increasingly proximate shocks to the system.

By what if polycrisis were the new status quo? While it is too facile to attribute a grand conspiratorial motive to the converging crises of the present, the global ruling class has, at minimum, recognized the pragmatic benefits of sustaining a state of perpetual polycrisis. By keeping the public in an incessant condition of uncertainty about the nature of reality, the ruling class is, paradoxically, able to retain its grip on power over the very global system ostensibly under existential threat from polycrisis.

The media serves as the handmaiden of this new perpetual polycrisis regime. In the 2020s, it seeks less to manufacture consent than to manufacture polycrisis. Indeed, any hopes of the return to a shared reality have been dashed in the age of the internet and social media, but the status quo can still be maintained by other means. You may not ascribe to the same reality as your neighbor, but both of you can agree that your sense of reality is under threat. Maintaining a sense of inevitability to this state of perpetual polycrisis is an essential component of the current ruling class ideological strategy.

The Inevitability of Technological Progress: A Model for Perpetual Polycrisis

My argument could simply stop here with the conclusion that the media manufactures perpetual polycrisis in order to secure the power of a ruling class now deprived of its ability to reliably manufacture consent. But, if you’re with me this far, I want to go a step further and ask why the manufacture of polycisis has become such a successful strategy for the 2020s ruling class.

At the core of perpetual polycrisis is the idea of inevitability. Political discussions are reframed from “What is the best way to end this crisis?” to “This crisis cannot end.” When this rhetorical move is applied to multiple converging crises, Tooze’s “world of the polycrisis” has arrived. In this world, the future cannot be different from the present; it can only look like the present on steroids. Crises cannot end, they can only multiply and compound.

I want to suggest that this logic of the perpetual polycrisis takes as its model the argument for the inevitability of technological progress. This argument has been on display most recently in the academic and journalistic discourse on artificial intelligence. Rarely ever do discussions on AI address whether this technology should be further developed in the first place. Instead, they focus on ways to “regulate” AI to make it “safer” and more “inclusive.” Underlying this narrative is the idea that the development of AI is inevitable and that all we can do is adjust and adapt to a world in which AI plays an increasingly prominent role in every facet of our lives.

In a world where novel technologies like the smartphone increasingly entice various social strata across the globe through what

calls the “mirage” of convenience, the argument for the inevitability of technological progress holds significant sway in the public. When everyone from rickshaw drivers in Delhi to billionaires in Manhattan rely on the same technological instrument for daily activities, it seems nearly impossible to reject the practical weight of the case for inevitability.But reject the ideology of inevitability is precisely what we must do. The manufacture of perpetual polycrisis draws its strength from the argument for the inevitability of technological progress. In this framework, the expansion of smartphones or AI is not a choice to be made, but, instead, a law of nature to be accepted. We may be aware of and even resent some of the deleterious effects of these technologies on our lives, but the ideology of inevitability insists that they are here to stay—forever. You can never resist, only adapt.

Likewise, we may oppose our government’s policy of funding and fueling endless wars in Ukraine and the Middle East, but we are told that, regardless of what we think about these conflicts, they are here to stay. Indeed, the manufacture of perpetual polycrisis relies on the same sense of disempowered fatalism inculcated by the argument for the inevitability of technological progress. Any critique of manufactured polycrisis, therefore, must first ground itself in a critique of this ideology of inevitability.

Integrating the Critique of Technology and Crisis

What might this look like in practice? The critique of technological inevitability and the critique of crisis must, first and foremost, be brought together.

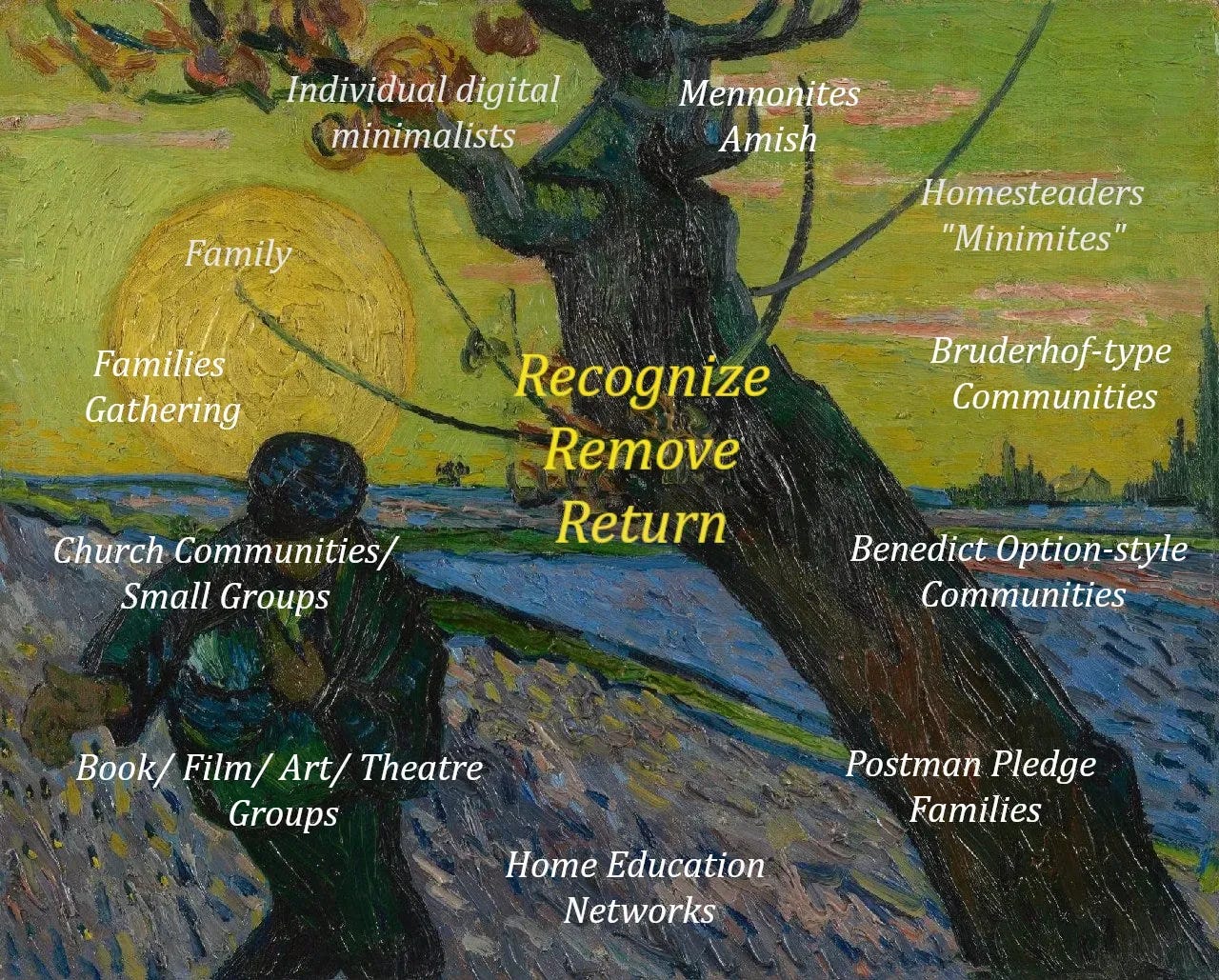

In their essay, “The 3Rs of Unmachining: Guideposts for an Age of Technological Upheaval,”

of and of provide some practical reflections on overcoming the inevitability ideology in our personal lives. Elsewhere on Substack, writers like , , and have offered formidable philosophical critiques of the inevitability of technological progress and its related constellation of ideological formations.

The critique of technological inevitability is foundational to any truly radical (in the sense of root cause-oriented) movement in the 2020s. But to create a world worth living in—to build a future beyond a more crisis-ridden version of the present—this critique must be connected to an understanding and analysis of the way in which the media manufactures perpetual polycrisis. Just as any critique of the perpetual polycrisis regime that ignores its roots in the ideology of technological inevitability is insufficient, the critique of technological progress must also address the pressing issue of manufactured polycrisis. In other words, the critique of technology must be integrated with the critique of crisis.

The shoes-off rule at American airports may seem trivial in the face global polycrisis. But the fact that it now feels second nature should serve as a warning to us all. Yesterday’s new policies (or pandemics or wars) can quickly begin to feel like today’s natural laws. The first step toward combating the perpetual polycrisis regime is to reject the fatalistic ideology of inevitability that undergirds it.

Very helpful in unpacking the concepts of polycrisis, inevitability of crisis and technological developments. Thank you!

The most inevitable force is the desire and intent of the powerful to control others. The tools they use may evolve and adapt, but their intent remains the same. Manufacturing consent becomes manufacturing polycrises, but the end is the same-control.

We've always been at war with Eastasia.