The “Free Speech” Right Embraces Cancel Culture

Why the justification for freedom of speech matters

Since I published “Why Free Speech?” here on Handful of Earth, I have been working on a Part 2. This follow-up essay is nearly complete, but it will have to wait. This is because the events in Israel and Gaza have added a whole other dimension and, I think, urgency, to the question of free speech. I want to address these events directly now and save my continued philosophical reflections for later.

Whatever your views of the conflict may be, I will focus here on the response in the United States. Thousands of human lives have already been lost and the conflict risks spirling into a broader regional or even international conflagration with direct American involvement. Therefore, I take it as self-evident that the response to the current situation among American political commentators, journalists, academics, and public intellectuals is incredibly important and has the potential to significantly impact the evolution of public opinion and government policy surrounding the war.

I chronicled my own intellectual and political trajectory on the question of free speech in “Why Free Speech?” Due to my background on the left, the reflections in that essay and elsewhere on Handful of Earth have highlighted the contradictions within leftist approaches to central political, cultural, and technological problems. What’s more, because of my writings on covid, I have likely attracted an audience more readily associated with the right of the American political spectrum than the left.

As a result of these and other factors, my own political positioning on “the right” or “the left” is not abundantly clear. I agree with the general contour of

’s 2022 New York Times column, “How the Right Became the Left and the Left Became the Right.” I believe that in a post-Trump and especially post-covid world it has become harder and harder to fit politics into the tidy left/right boxes constructed in the historical crucible of the bourgeois and socialist revolutions.All of that said, it is undeniable that that the majority of attacks on free speech (especially “free speech culture”) in recent years have come from the contemporary “left.” In many ways, the contemporary “right” (despite its own internal contradictions) has stood as a bulwark against a complete collapse of free speech in the United States, especially on hot button issues such as the pandemic and the war in Ukraine.

Because of my own opposition to covid mandates and the American proxy war in Ukraine, the contemporary right’s role in keeping some semblance of debate on these issues alive has been indispensable. But here I want to suggest that one’s reasons for holding a particular dissenting position matter just as much as the position itself and the politically malleable rhetoric of “free speech” employed to justify it.

Particular positions don’t always reveal the reasons behind them, reasons which only begin to become clear when emerging scenarios and events present new challenges to existing political formations and alignments.

The escalation of violence in Israel and Gaza has presented one such challenge. Specifically, this challenge has been presented to the “free speech” right which has, barring some exceptions, miserably failed. Allow me to provide several examples:

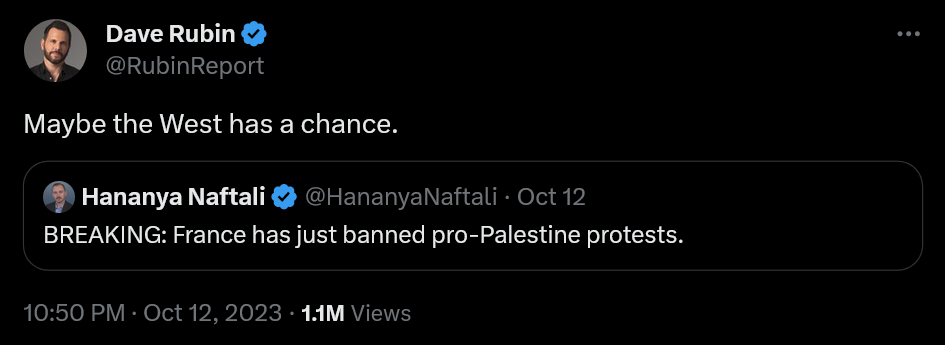

Dave Rubin, conservative political commentator and co-founder of Locals, a self-described “free speech platform” that will “never ban people for their political stance or personal opinion,” had the following to say about France’s move to ban pro-Palestine protests:

Shortly before writing this, Hanania published another article on his Substack entitled, “The Ethical Case for a Siege of Gaza.” In it, he admits that his classical liberal assumptions break down when he attempts to analyze geopolitical conflicts. Clearly his classical liberalism didn’t work to uphold a culture of free speech, either. At least Hanania is honest about his own hypocrisy, unlike many other commentators.

And then see the response from Free Press writer, Maya Sulkin:

At the University of Washington, a crowd of Students for Justice in Palestine filled the air with chants of “There is only one solution” as a Jewish student cried and begged an administrator, “They want us dead. How are you allowing this?” Olivia Feldman, the 20-year-old co-president of Students Supporting Israel at the college, told The Free Press, “I’ve been called a terrorist and a colonizer. I’ve been called a baby killer in the past. A lot of students are really afraid to go to class tomorrow.”

Instead of simply presenting the book’s merits, Haidt—in a rhetorical move reminiscent of the social justice warriors he detests—decides to connect the importance of the book to the present situation in Israel and Gaza:

The Canceling was a darn good book when I read a draft last spring, in order to write the Foreword for it. It’s an even better book now that the world has been treated to the shocking spectacle of so many university presidents remaining silent, or issuing only vague and cautious comments, in days after the October 7 terrorist attack on Israel. Their collective reticence stood in stark contrast to the speed with which so many had offered expressions of solidarity or shared grief whenever an election or court case went the “wrong” way in the years since 2014.

Haidt makes no mention of the actual cancellation of students and others who have criticized Israel following the escalating violence in the region. Instead, he seems more concerned about purported university administrative silence in condemning Hamas, and even flirts with an argument for compelled speech on the topic in light of previously set precedent.

Though Haidt claims that he’s in support of “institutional neutrality” in academia, he’d prefer that the neutrality begin after he receives emotional validation from strong administrative statements on his side of the issue currently occupying the global news cycle.

I could mention other examples, but I hope these suffice to make my point. What we are currently witnessing is a symptom of the problem I pointed out in “Why Free Speech?”: a weak argument for freedom of speech is vulnerable to attack.

I believe that the classical liberal argument for free speech is a serious one that demands equally serious philosophical and political engagement. It’s not easy to see its flaws, and that’s why I devoted the better part of a lengthy essay to bringing these flaws into focus. What I didn’t expect was the emphatic falsification of the classical liberal argument for free speech in practice by its own proponents, some of whom I’ve mentioned above.

Indeed, the failure of the “free speech” right to uphold its own professed principles should serve as a warning to us all. When powerful players beat the drums of war, emotions run high. If we’ve learned anything from the War on Terror (apparently many haven’t), we should realize just how easy it is for generally well-intentioned, rational people to become possessed by the thirst for vengeance and, in the process, trample on their own purported values.

Beyond these urgent political problems, there is the equally urgent philosophical task of providing an argument for free speech that is strong enough to withstand the inevitable challenges posed by events such as the current ones unfolding in Israel and Gaza. I will move in that direction in Part 2 of “Why Free Speech?”

Politics is downstream from ethnos. Understanding that clears up a lot of what looks on the surface to be hypocrisy.