The Tyranny of the OTP

Against the technological takeover of private life

I remember the first time I used a one-time password (OTP). It was in India in the mid-2010s. I was logging onto my bank account and was prompted to verify the validity of my login via a text message OTP sent to my phone. The new OTP ritual started with banking services, but soon began to be a part of online purchases, website logins, and a host of other internet activities.

At the time, I thought that the OTP was an idiosyncrasy of a country whose population had, by and large, leapfrogged over the personal computer straight to the smartphone. Most everyday online actions in India are performed on smartphones—which began to rapidly proliferate in the country in the late-2010s—rather than on desktop or laptop computers. It made sense that the OTP, linked, as it usually is, to the mobile phone SIM card, would be well suited to a country where the device for online activity and identity verification was one and the same.

However, when I returned to the United States, the OTP had begun to expand its dominion from the Third World to the First. It consolidated its newfound power during the pandemic and now appears to be here to stay (at least until the next trend in personal cybersecurity emerges). In a world where apps like WhatsApp dominate the personal messaging space, my SMS history is now a sea of OTPs.

The OTP may seem like a trivial thing to write about or (as the title of this essay suggests) resist. After all, how different is it from the older convention of passwords, which we had to remember or write down in order to access various websites and services online? There do appear to be security advantages to the OTP in comparison to long-term passwords, which can be more easily hacked and stolen over time. However, even if we take ostensibly enhanced security as a given, is the OTP an entirely innocuous innovation?

The OTP is a small but, I believe, significant step on the long path toward the technological takeover of private life. It is hardly the first one and surely won’t be the last. Today, it feels like a footnote to technological developments in artificial intelligence. But it is precisely the mundanity of the OTP—its prosaic unremarkableness—that allows a technology like this to enter our daily lives without notice, fanfare, or resistance.

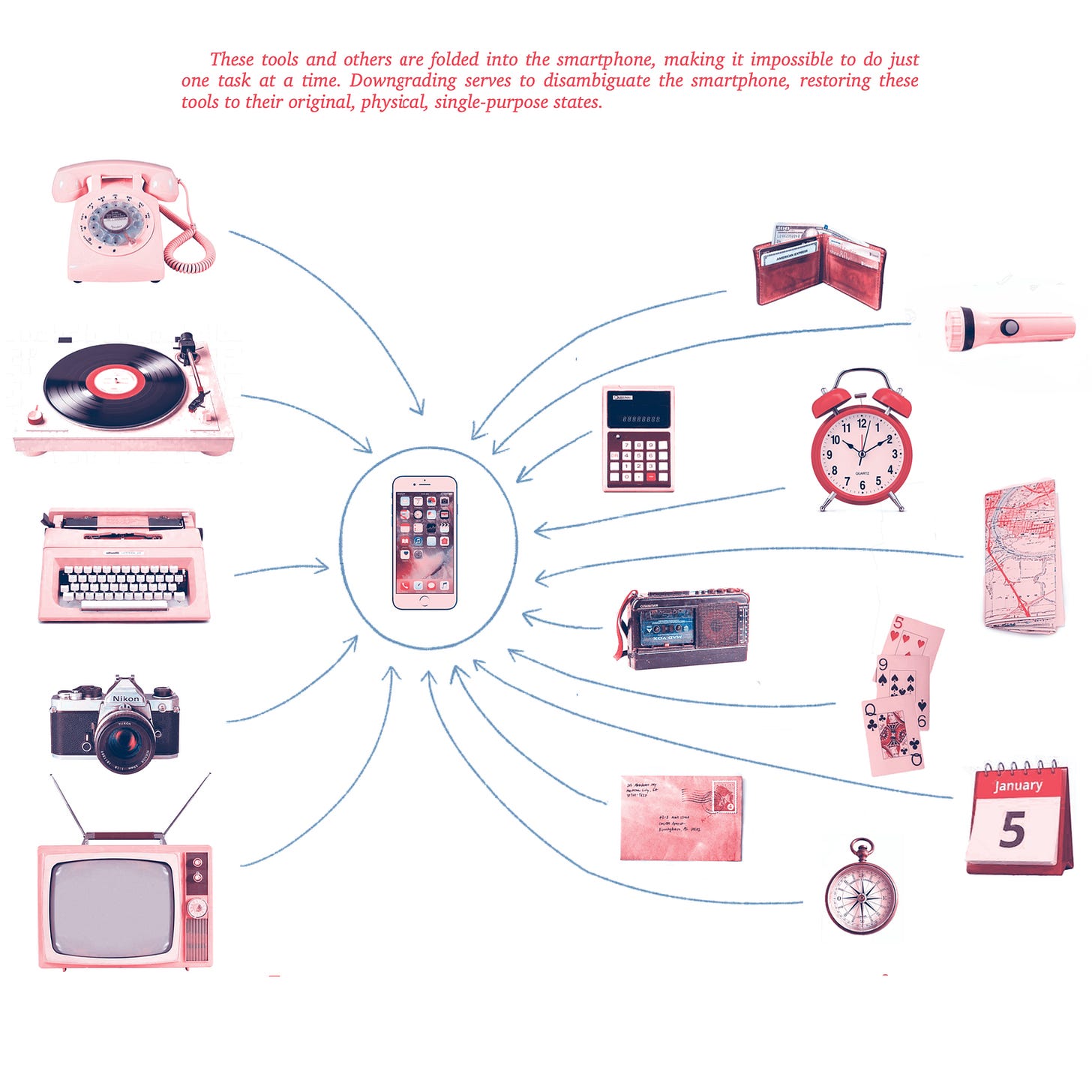

Commentators have noted the tendency of the smartphone to take what were previously separate activities carried out at separate locations or on separate devices and put them on one singular device. Whereas one used to listen to music on a record or CD player, watch TV on a television, meet potential partners at a bar, gamble at a casino, and order food at a restaurant, the smartphone has combined all of these activities (and more) on one mobile device. Less often observed, however, is the way in which the smartphone has become increasingly necessary in order to use other devices.

I turn my phone off at night and, on days that I am working from home, I like to keep it off for the first few hours of the morning. I usually do offline activities at this time, but sometimes I use my computer. This used to be quite easy to do since my phone felt like a separate entity from my laptop. However, after the ascent of the OTP, maintaining this division has become increasingly difficult. Even previously straightforward logins now often require an OTP to be sent via SMS to the user’s phone, demanding that I then turn on my phone in order to continue working on my computer. The computer is no longer its own independent tool; rather, it is subordinate to the mobile phone, which now creates the conditions of possibility for its use.

I say “mobile phone” here rather than “smartphone” because the SMS-based OTP system does not technically require a smartphone. A Nokia 3310 can get the job done. However, the normalization of linkages between the personal computer and the mobile phone via the OTP has now given way to further efforts to make the computer dependent on the smartphone. Despite its security advantages over regular passwords, SMS-based OTPs are still subject to significant threats from SIM swapping and hacking, account takeover, lost and synced devices, and phishing. As an alternative to the standard text message OTP, recent years have been witness to the proliferation of “authenticator apps” which rely on smartphone applications rather than SMS to verify the identity of the user. The result is an increasing subordination of the computer to the domination of the smartphone.

The rise of the OTP and authenticator app doesn’t just represent the domination of the smartphone over other devices. It also represents the intrusion of the public world into private life. The standard password is something that is possessed by the individual. To log into a website with such a password is to engage in what at least feels like a private interaction with the site or account in question. The interaction is mediated by your memory or password list. The OTP, on the other hand, offers a constant reminder of the specter of the public gaze on our private activities. When you unlock your phone, look at the OTP, and enter it, you are told that online activity isn’t, in fact, private—there is some greater entity, or authority, that determines whether you have the right to access the website. Are you stealing someone else’s identity? Are you really who you say you are? Enter the six digits and prove it.

Whatever that authority is—the state, the corporation, the algorithm—it is keeping tabs on you. This is for your own good, we are led to believe, since security breaches are rampant online. We are not supposed to ask why we have vested so much of our private information and lives in digital technologies that are, by their very nature, so ephemeral and insecure that constant security protocols are required just to ensure a modicum of safety in the completion of daily tasks.

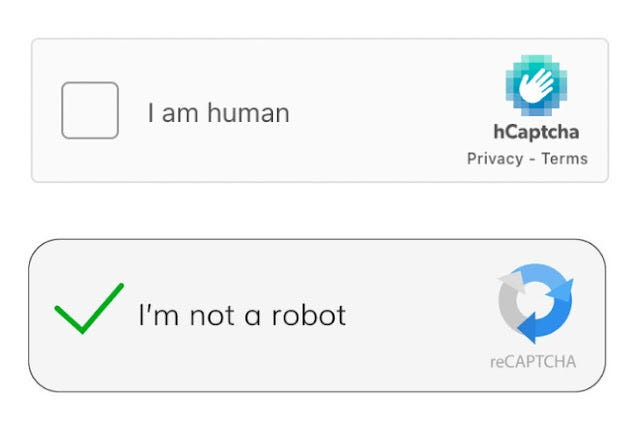

With the advent of online bots and AI, the increasing prevalence of the CAPTCHA has produced new absurdities. It is now par for the course to check the box “I am not a robot” or “I am human” to access many websites. In order to prove my humanity, I often find myself doing tasks that I suspect the latest AI could complete with far more accuracy and efficiency. The latest example I can remember was being told to click on the parts of an image where a bicycle was visible. Perhaps I didn’t do well enough since I was then prompted to the same with a bridge.

The OTP questions whether you are actually the human being you say you are. The CAPTCHA, though confined to one device, goes a step further and asks whether you are human at all. It then proceeds to degrade the very concept of humanity by demanding that you perform tedious robotic tasks to prove that you are, indeed, a human being.

writes that “Privacy comes from the awareness that some official limit has been surpassed, some unlicensed space shared.” The message of the OTP and the CAPTCHA is that every space must be licensed or else it is unsafe. In the name of security, privacy is destroyed.What would it take to enter “the world of privacy” which Simon defines as “the space for unmediated words and thought”? With or without the OTP, the internet is a poor substitute for the intimacy of a close friendship or sexual relationship in which, as she puts it, the “‘Oh wow, you too?’ response of another is what assures us of our own capacity for a private space of our own.” We intuitively know that technological mediation increasingly encroaches on our capacity to hold this private space, but it is difficult to identify exactly which technologies have created forms of mediation that necessarily impinge upon our ability to enter the world of privacy.

It has become justifiably popular to bash on the smartphone, but I believe that the technological assault on private life has a much longer history. If we take seriously the capacity for technology to radically transform our very being in the world, we must pinpoint—to invoke Karl Marx’s distinction—which technologies have served as mere tools and which have taken on the status of machines. For Marx, machines, unlike tools, are “emancipated from the organic limits” of human biology and, therefore, radically reshape humans’ relationship with ourselves and the world.

I want to suggest here that the advent and spread of the home phone—long before the mobile phone and the smartphone—was a turning point in reshaping human understandings of communication. This change in our conception of communication, in turn, contributed to the erosion of our private lives.

The first domestic telephones were introduced in the late nineteenth century and became much more widespread in the twentieth century. According to United States census data, 2 percent of American homes had a telephone in 1890, 35 percent in 1920, 41 percent in 1930. Interestingly, the number dropped back into the 30 percent range during the 1930s. It then bounced back and, by the 1960s and 1970s, the home phone had become nearly universal in American households.

Before the home phone became the new normal, letter writing was the predominant form of communication when face-to-face interaction was not possible. The act of reading and writing letters in itself created a clear distinction between in-person interaction and long-distance communication. Because letters required a protracted ritual of asynchronous activities—deciding to write a letter, writing the letter, addressing the envelope, mailing it, and waiting for a response after the reader went through his or her own corollary process—it was impossible to mistake the interpersonal connection forged through epistolary correspondence with that of in-person connection. It was a qualitatively different experience. Letter writers, I suspect, did not feel the urge to stop meeting up with people in real life because they thought that their habit of letter writing was an adequate substitute.

The practice of epistolary correspondence also cultivated everyday worlds of privacy for letter readers and writers. Though the goal of sending a letter is, of course, communication with another human being, the nature of the communicative experience is profoundly private: the writer and reader write and read privately, fostering a form of interpersonal communication rooted, perhaps paradoxically, in an obligatory form of interiority. The transport of a letter from sender to recipient is also easily intelligible—it must be brought from one physical location to another. The time lag between sending a letter and receiving a response is a constant reminder of the organic limits of human engagement with the environment and the physical distances between real places.

The home phone changed this intuitive understanding of communication forever. By creating the possibility of synchronous long-distance communication from the comfort of one’s home, the domestic telephone opened up the Pandora’s box from which a host of other modern technologies sprang. The status of the home as a space for face-to-face interaction with family, friends, and neighbors in addition to its role as a place for individual solace and reflection was irrevocably transformed by the home phone. The home phone brought the public world squarely into the realm of everyday private life. All of a sudden, the wider social world was instantly accessible without leaving the house. Letters began to feel like an antiquated and inefficient form of communication. They died a slow and painful death before being put out of their misery by email and instant messaging in the 1990s and 2000s.

The history of modern technology is the story of the replacement of tools by machines. This process is characterized by increasing levels of abstraction. The act of a courier delivering a letter makes intuitive sense—whatever the means of transportation, the letter is carried from point A to point B, delivered, and the process is repeated if the recipient chooses to respond. The landline phone represents an early, but crucial, form of abstraction by changing our understanding of the relationship between communication and time. No longer is communication exclusively achieved in face-to-face interactions or by the physical transport of physical letters—it can now be done at a distance through wires whose properties are unknown to the everyday user. With the advent of mobile phones, communication became possible through much more inscrutable wireless technologies. The internet and the smartphone are but the latest iterations in this process of abstraction. Both technologies have become a focal point in many of our lives, but most of us have no idea how or why they work.

Besides serving as a recent example of public penetration into private life, the OTP illustrates how abstracted communication has become in the twenty-first century. Contemporary digital platforms that provide the means of online communication aren’t “set and forget” technologies; instead they require constant validation of the user’s identity through a black box of increasingly integrated networks of devices and data. While the techno-dystopian “Internet of Things,” defined as “the vast array of physical objects equipped with sensors and software that enable them to interact with little human intervention by collecting and exchanging data via a network,” may seem like a far cry from the OTP or authenticator app, the OTP plays a critical role in normalizing the necessity of interconnected digital devices to carry out previously independent tasks.

For those of us whose livelihoods depend on the internet, it is difficult not to simply go along with OTPs, authenticator apps, CAPTCHAs and whatever the next iteration of digital identity verification may be. Perhaps there will be a point where something about the forthcoming technology itself compels us—on ethical, political, or spiritual grounds—to refuse to use it entirely. That is a question for us to reckon with both individually and collectively. The most urgent task today is, I believe, to become aware of the ways in which these technologies have shaped and continue to shape our understanding of communication, privacy, and the human being. This essay is one effort to that end.

In a media age increasingly dominated by audiovisual content, we can also consciously choose to revive practices such as epistolary correspondence. AI evangelists promise a world in which the acts of reading and writing can be fully automated or replaced by audiovisual media. This is a future foretold by the home phone, which made the most personal form of reading and writing—the letter—obsolete. However, Jason Read argues that reading is not “just one technology among others when it comes to the retention and communication of thoughts.” Read writes that one can

just as easily make an audio or visual recording of…ideas as something to share with others…The difference between these different ways of recording is how each relates to time. Videos and audios have their own time span, a film is ninety or a hundred and twenty minutes, a podcast an hour or more, and so on. That cannot change without distorting it…When I read, however, the timing of the reading is more undetermined and less hardwired into the technology, if it does not sound too weird to call writing technology…Reading has a unique relationship to the time of thinking. In some sense reading is thinking.

Our world of privacy is cultivated by activities like epistolary correspondence (and reading and writing more broadly). Reading and writing fosters a sense of interiority—which demands privacy—that is not antagonistic to interpersonal relationships but, rather, nourishes them. To resist the tyranny of the OTP and, indeed, the tyranny of its many predecessor and successor technologies, we must reclaim this sense of interiority. James Baldwin’s words ring true: “Though we do not wholly believe it yet, the interior life is a real life, and the intangible dreams of people have a tangible effect on the world.”

This article makes me want to write out letters and start sending them off. I've noticed the arrival of the OTP as I've switched to a flip-phone that hinders certain capacities, yet gives me so much more free time (self-control is hard in the Dopamine Age).

Here's hoping the Technofeudal Age is not preparing to wash us all away.

#StayHuman

Fucking hell, this should be in the New Yorker or something. Brilliant piece.