Weekly Grounding #106

News, links, writing

Weekly Groundings are published every Friday to highlight the most interesting news, links, and writing I investigated during the past week. They are designed to ground your thinking in the midst of media overload and contribute to Handful of Earth’s broader framework. Please subscribe if you’d like to receive these posts directly in your inbox.

If you’re already subscribed and want to help the publication grow, consider sharing Handful of Earth with a friend.

“Bots Now Make Up the Majority of All Internet Traffic”

The Independent reports on the AI takeover of the internet: “Analysis by cyber security firm Imperva revealed that automated and AI-powered bots accounted for 51 per cent of all web traffic in 2024, with so-called ‘bad bots’ at their highest level since the firm started tracking them in 2013. The researchers noted that the emergence of advanced artificial intelligence tools like OpenAI’s ChatGPT and Google’s Gemini have led to new cyber threats for web users…These AI tools can be used to carry out spamming campaigns or even distributed denial-of-service (DDoS) attacks that knock sites offline by overwhelming them with fake traffic.”

The 2025 Imperva Bad Bot Report notes that the “industries most at risk…are financial services, healthcare and e-commerce. The report tracked an average of 2 million AI-enabled attacks each day last year, with the Bytespider web crawler tool making up 54 per cent of them. Developed by TikTok owner ByteDance, the ByteSpider bot’s dominance was attributed to its widespread recognition as a legitimate tool, which the researchers said made it an ‘ideal candidate for spoofing.’”

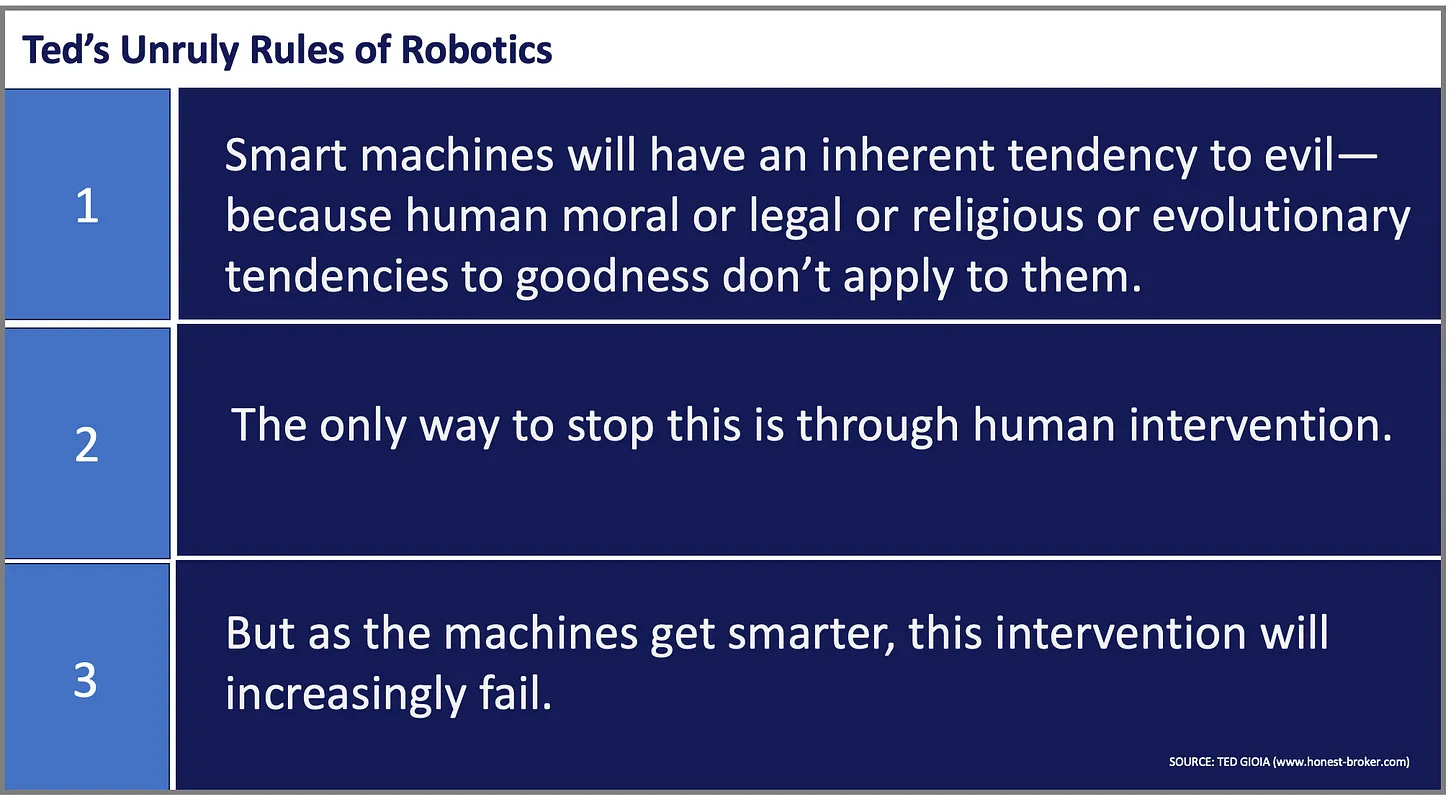

“As AI Gets Smarter, It Acts More Evil”

Meanwhile, at

, argues that “we should see evidence of AI acting more evil with each new generation of bots.” Gioia believes that this is because “AI doesn’t make ethical decisions like a human being. And none of the reasons why people avoid evil apply to AI.” He proposes a hypothesis on the future trajectory of AI:Gioia believes that “There are only two reasonable responses to this: (1) Limit the sphere of influence of machine thinking, or (2) Impose fail-safe constraints at a macro level—let’s call it a kill switch—that can save us in a crisis. If we don’t do this, that crisis is inevitable. And even if I like reading those dystopian sci-fi book scenarios, I don’t want to live inside them.”

“Why Jeffrey Epstein Matters Economically”

At The Financial Times, Rana Foroohar writes that Jeffrey Epstein’s “associates were an equal opportunity group of elite Republicans and Democrats (along with the occasional royal) representing those who’ve benefited most from the neoliberal economic policies of the past half century. If you were riding as an associate on Epstein’s plane, or meeting with him on his private island, or discussing cross-border financial deals with this predator, then you are by definition part of the educated, mobile tribe that writer David Goodhart famously dubbed ‘anywheres’ who operate at 35,000 feet above the economic concerns of most people in most nation states.”

She continues: “Most Maga supporters (but certainly not all) are ‘somewheres,’ meaning they are more rooted in place, whether by choice or by force. Many of the places they come from are suffering and have suffered disproportionately from neoliberal thinking propagated by the mainstreams of both political parties. It’s richly ironic that Trump’s own ‘big, beautiful bill’ was the culmination of this, with tax breaks for private equity paid for by cutting healthcare benefits for poor people. Meanwhile, his Genius Act will undoubtedly be the fuel for the next major financial crisis…”

“Tequila, Drugs and Torture: The Spending Binge of Two Crypto Bros That Ended Behind Bars”

The Wall Street Journal reports on the dark underbelly of elite crypto culture: “William Duplessie, a 33-year-old college dropout and crypto investor, and...John Woeltz, 37, a cryptology and cybersecurity specialist from Paducah, Ky.,...set out to ingratiate themselves with members of some of the wealthiest, most influential families in America. The two men were on a mission that, whatever it was at the start, disintegrated into a weekslong binge of cocaine, booze and spending. It ended in May with arrests and allegations of kidnapping and torture within the posh confines of a $75,000-a-month rental in Manhattan, according to witnesses and courtroom testimony.”

The article states that “Duplessie and Woeltz claimed to have a trove of crypto capital ready to invest…One acquaintance said the men talked up plans to buy land and develop western Kentucky’s economy, investing in hydroelectric dams and a luxury hotel. Duplessie, who had the state seal tattooed on his chest at some point during the festivities, was weighing a long shot bid for the Senate seat of former Majority Leader Mitch McConnell (R., Ky.).”

“On May 23, a 28-year-old cryptocurrency trader from Italy ran shoeless and bleeding from Duplessie and Woeltz’s eight-bedroom townhouse in Manhattan and begged a New York City traffic cop for help. He said the men had held him for more than two weeks, using torture to try to pry loose passwords to his cryptocurrency accounts. They dangled him from the top of five flights of stairs, threatening to kill him if he didn’t cough up a ransom, the man alleged in a criminal complaint. Lawyers declined to comment on behalf of Duplessie and Woeltz, who have pleaded not guilty to charges of assault, kidnapping and coercion.”

“On Being Hated”

At her eponymous Substack,

reflects on hatred and being hated: “If we are not to hate the sinner, we might nevertheless hate the sin. This hatred is predicated on the idea that there are better and worse ways to live and behave, and that we are all capable of sinning, but also of avoiding or resisting sin. A liberal anti-Christian culture imagines that by eliminating the category of sin, we might thereby prevent the need to stop doing it. This idea only works if we imagine that we are an entirely blank kind of creature who can be shaped at any moment by whims and fancies. But we are not. We have a nature.”Power continues: “How we mercifully adjudicate (human) justice is one of the hardest questions to answer, both in the abstract and in the particular. But forgiveness is possible; atonement is possible; making amends is possible. Restoring balance is possible (if rare). It is a terrible waste of one’s life to be consumed with hatred, or to wish to be a victim, even if one has been victimised. Christ’s sacrifice was the last one: his victimhood incomparable—this releases you from the burden of being both apex victim and apex executioner. We are all both, all the time, and there is light even in the darkest of rooms.”

She concludes: “There is a curious and wonderful feeling attendant on being hated that is hard to describe, but it is something like no longer having to worry that one day you might be hated.”

“Math Is Erotic”

reviews J. Jacob Tawney’s book, Another Sort of Mathematics, for First Things: “His book arrives at a time when it has become necessary to rethink education altogether. David McGrogan at News from Uncibal writes about ‘the coming competence apocalypse.’ The likely atrophy of our mental faculties from outsourcing mental tasks to AI will only accelerate the long-running collapse of competence that McGrogan details. Meanwhile, John Carter at Postcards from Barsoom likens the state of the university to that of the monasteries in late-medieval England, where, he writes, ‘religious vows were more theoretical than daily realities for many monks. Does anyone truly think that Harvard professors take Veritas at all seriously?’”Crawford writes that the “function universities have long played is less one of educating than of credentialing. Carter gives us good reason to think the credentialing function of universities is about to collapse, due to AI. But he finds new possibilities, or rather old possibilities, emerging from the wreckage: liberal education in the original sense, as a leisure activity (‘scholar’ is from schole, leisure) for its own sake; for the love of truth. Unburdened of its current gatekeeping role in the political economy of managerialism and bullshit jobs, and no longer serving as a legitimation operation for unpopular political projects (producing ‘the Science’ that must be ‘followed’), the successor to the modern university will be something subterranean rather than publicity-seeking, disconnected from power and money, useless, a place where people with the most searching minds gather to pursue truth for the love of it, as literal amateurs.”

Crawford argues that “The purely mental activity of doing mathematics can be a mode of access to something that transcends the human mind. That this should be the case would seem to indicate that there is a deep resonance between mind and cosmos—almost as if cosmos participates in mind…Tawney says in Another Sort of Mathematics: ‘There is something unique in the human soul that can only be satisfied by wondering about mathematics.’ He says this is because we are oriented to the good, the true, and the beautiful. That human beings should have an ‘orientation’ toward anything at all is the controversial thing here. We call that ‘teleological thinking,’ and it is a bit disreputable. But Tawney insists math is good prior to any application or usefulness or ‘relevance’ it may have, such as the STEMmers emphasize. Might this goodness be due to the resonance that math reveals between mind and cosmos? In Greek, cosmos means ‘order,’ and suggests also ‘beauty,’ as in our word ‘cosmetic.’ Doing math leads one to entertain the idea that the cosmos is itself good and beautiful. Our will to truth seems to derive from a deep attraction to this goodness and beauty. Math is erotic, in other words. Tawney’s metaphysics are unapologetically Platonic. This is an excellent position from which to begin to recover the possibility of real learning, as the machinery of fake expertise and empty credentials crumbles around us.”

What grounded your thinking this week? Share in the comments.