Weekly Grounding #53

Special edition on the economy

Weekly Groundings are published every Friday to highlight the most interesting news, links, and writing I investigated during the past week. They are designed to ground your thinking in the midst of media overload and contribute to Handful of Earth’s broader framework. Please subscribe if you’d like to receive these posts directly in your inbox.

Each Weekly Grounding generally touches on a wide range of topics related to Handful of Earth’s broad focus on culture, politics, and technology. This week, however, I happened to read a number of interesting pieces on economic issues, so decided to make this a Special Edition on the economy. This is the second Special Edition Weekly Grounding—the first was on the topic of artificial intelligence (#43).

“Degree? Yes. Job? Maybe Not Yet.”

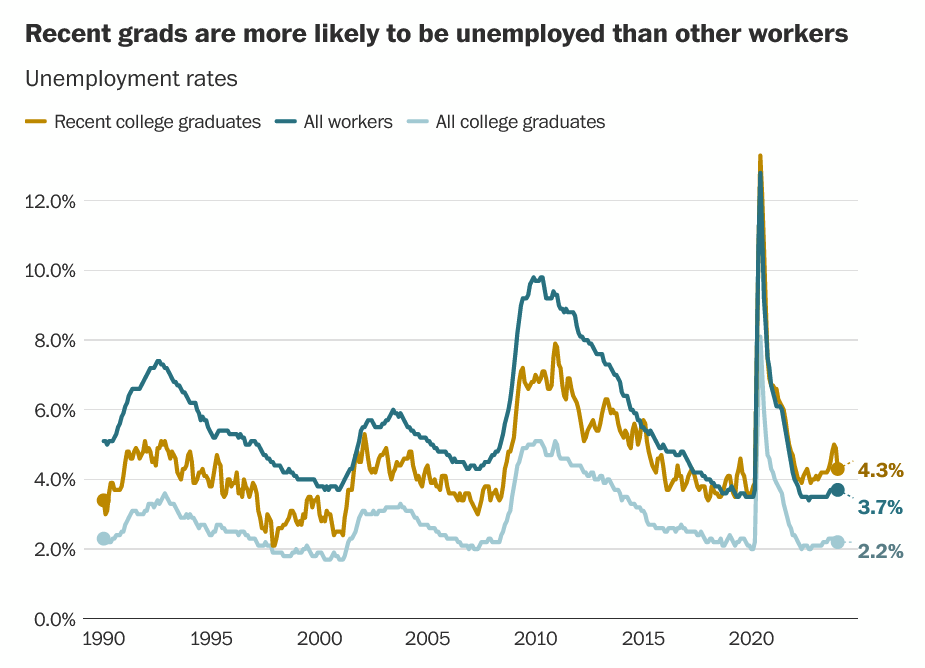

The Washington Post reports on recent college graduates’ struggles in the job market: “[T]he U.S. unemployment rate for 20- to 24-year-olds has climbed sharply in the past year, from 6.3 percent to 7.9 percent as of May — the largest annual increase in 14 years, excluding the early shock of the pandemic. That setback is just the latest hitch for the 2 million people projected to get bachelors degrees this year. Many started college in 2020 by logging into Zoom classes from their childhood bedrooms instead of moving into dorms and clambering into lecture halls. They’ve missed out on internships and in-person mentorships, and in many cases are graduating with thinner resumes than their predecessors.”

The article continues: “And although for most of the 1990s and early 2000s, a newly minted college degree came with a better-than-usual shot at employment, that’s changed in recent years. Today’s recent graduates ages 22 to 27 have a higher unemployment rate — 4.7 percent, as of March — than the overall population, according to an analysis by the New York Fed.”

“Social-Media Influencers Aren’t Getting Rich—They’re Barely Getting By”

The Wall Street Journal takes a deep dive into the rapidly transforming economy of short-form social media content: “Earning a decent, reliable income as a social-media creator is a slog—and it’s getting harder. Platforms are doling out less money for popular posts and brands are being pickier about what they want out of sponsorship deals. The real possibility of TikTok potentially shutting down in 2025 is adding to creators’ anxiety over whether they can afford to stick with the job for the long haul.”

The report notes that, during the pandemic, “A small number of creators shot to fame, propelling the occupation to the top of career wish lists for many teens (and adults). But behind the scenes, creators say the job is grueling. They need to constantly produce compelling posts or risk losing momentum. They spend their days planning, filming and editing posts while also working to make inroads with advertisers and interacting with fans.”

It used to be easier for aspiring influencers to earn money directly from social media platforms. But even when the money was flowing, these platforms always reserved the right turn off the spigot, a right which they’ve recently exercised to the dismay of their content creators: “TikTok’s $1 billion creator fund, which ran from 2020 to 2023, doled out money to eligible creators for posting to the platform. Others joined in. YouTube’s TikTok competitor, Shorts, allowed creators to earn anywhere from $100 to $10,000 a month with its temporary fund. Instagram’s Reels Play bonus program rewarded creators with fluctuating payouts. Snapchat’s SNAP 0.79% increase; green up pointing triangle Spotlight rewards program gave $1 million a day to the platform’s top creators. Today, the platforms have revamped or completely changed how they pay creators—doing away with their funds.”

“Global Defense Groups Hiring at Fastest Rate in Decades Amid Record Orders”

If jobs for recent college graduates and income for social media influencers are both drying up, the same cannot be said of the defense industry, which is booming as a result of wars in Ukraine and Gaza. The Financial Times reports that “Global defence companies are recruiting workers at the fastest rate since the end of the cold war as the industry seeks to deliver on order books that are near record highs. A Financial Times survey of the hiring plans of 20 large and medium-sized US and European defence and aerospace companies found they are looking to recruit tens of thousands of people this year.”

According to Jan Pie, secretary-general of ASD, the European aerospace and defence trade association, “Since the end of the cold war, this is the most intense period for the defence sector with the highest increase in order volume in a rather short period of time.”

“Why Has Trump Stopped Attacking Big Business?”

At

, Matt Stoller compares the populist vocabulary and policies of 2010s Donald Trump with his significantly more pro-corporate 2020s persona. After a 2016 campaign in which “he feuded incessantly with corporate America, telling a story about big business as part of the corrupt establishment trying to outsource jobs and replace American workers with cheap labor,” Trump followed through on many aspects of his campaign rhetoric. He “withdrew the U.S. from the Trans-Pacific Partnership, renegotiated NAFTA, and raised tariffs on Chinese imports. The press pretended that this stuff was mostly fake, but it wasn’t. For instance, the Trump administration blocked imports of lumber from a Peruvian exporter based on concerns over illegal harvesting, the first use of environmental standards in trade law ever by the U.S. government. As another example, there’s now a wave of Mexican labor organizing spurred by the labor provision in the new NAFTA.”In contrast, post-presidential “Trump sounds like he is the coalition leader of the Republican establishment. He’s still funny, and he’s still weird, and still iconoclastic in terms of his personality. But in terms of what he promises, he’s mostly stopped challenging big corporations, except in cultural terms acceptable to Wall Street. At the Business Roundtable and elsewhere, for instance, Trump offered a cut to corporate income taxes and a rollback of rules on corporations, especially the oil industry.”

While Trump’s pivot away from economic populism does not seem to be hurting him in the polls so far, Stoller highlights the following Financial Times poll which indicates that Americans no longer view the former president as an economic populist:

“What Comes After Neoliberalism?”

In the wake of the Biden administration’s tariff increases on Chinese goods, Project Syndicate asks six mainstream economic thinkers whether neoliberalism is over and, if so, what will follow it. While all of the perspectives have serious limitations, a few excerpts are worth highlighting.

Dani Rodrik writes that “The neoliberal consensus has been overtaken by new concerns about geopolitics, national security, supply-chain resilience, climate change, and the erosion of the middle class. We should not mourn its passing, as it was unsustainable and had many blind spots. Whether something good comes out of it will depend on the nature of the response, which could be either reactive or constructive.”

Joseph E. Stiglitz notes that “The neoliberal agenda was always partly a charade, a fig leaf for power politics…That it was a charade has now been made apparent by the US, which is providing huge subsidies to certain industries – essentially disregarding World Trade Organization rules – after decades of scolding developing countries that even considered doing the same. Admittedly, the US is acting partly in the service of a good cause: the green transition. Nonetheless, its actions demonstrate that the powerful not only play a disproportionate role in making the rules, but also flout them when they become inconvenient, knowing that there is nothing that others can do it about it.”

While arguing in favor of neoliberal policies, Michael R. Strain admits that the economic policies promoted by Donald Trump and continued by Joe Biden are “post-neoliberal.” Strain notes, like Stoller in the above article, that “Trump broke with the bipartisan free-trade consensus.”

“Imprecise Truths About The American Caste System From My Own Experience”

At

, David Roberts explores “an aspect of inequality that involves more than gradations of wealth and income, namely the division of American families into two separate castes—the elite and everyone else.”He writes: “Given the parental imperative, the interplay between wealth and social capital, and the limited, if not fixed, availability of elite educations, jobs, and homes, I can’t see how the division between an elite class and all others won’t continue and accelerate…A solution to economic inequality aimed at people, mostly men, who don’t go to college is to emphasize the ‘trades,’ e.g., electricians and plumbers, as jobs that provide a good living without the necessity for a BA. But that will not solve class divisions. Women with college degrees, especially from a selective college, especially with an advanced degree, are unlikely to want to marry a man in the ‘trades,’ no matter how lucrative his income.”

He concludes with a short but deeply insightful statement: “Finally, as to who’s part of the elite and who’s not, I think I know an elite when I meet them. The characteristic they have in common is that their capital, both financial and social, gives them a sense of immunity, real or not, from life’s economic and status vicissitudes and thus great agency over their lives.”

What grounded your thinking this week? Feel free to share in the comments.

I liked the focus on economics and the selection was illuminating. The lay out was easier to follow with titles and good summaries.

Fascinating as always !