Weekly Groundings are published every Friday to highlight the most interesting news, links, and writing I investigated during the past week. They are designed to ground your thinking in the midst of media overload and contribute to Handful of Earth’s broader framework. Please subscribe if you’d like to receive these posts directly in your inbox.

“This Is Republicans Getting Desperate”

addresses the Trump campaign’s turn away from “heady philosophizing about industrial policy, right-wing unionism and ‘national conservatism’” toward “hatred of immigrants” at : “For all of their faults, the Republicans once at least had an actual message and platform to run on, unlike Kamala Harris. They’ve abandoned it. Their campaign is now predicated on instilling ordinary Americans with contempt and fear of powerless people and leveraging that hatred into votes. The pressure of actual political competition has reduced them to this pathetic spectacle.”Most importantly, Woodhouse points out the dangerous disregard for reality that characterizes recent Republication electoral talking points: “I’ve been seeing the defense raised on Twitter that the pet-eating allegation was some kind of a heuristic tool to bring attention to the issue of a small town buckling under the strain of a huge migrant influx, so it doesn’t matter if it’s factually true or not. This is what’s also known as a lie told for political gain, no different from liberals claiming J.D. Vance once fucked a couch. When Alexandria Ocasio Cortez said an interview, ‘I think that there’s a lot of people more concerned about being precisely, factually, and semantically correct than about being morally right,’ she was ridiculed and excoriated by her conservative critics. Now they’re making the exact same defense of Trump, Vance, and their online supporters.”

“Wolfgang Streeck: “Sahra Wagenknecht Is the Only One Asking the Right Questions—and Offering the Right Answers”

Die Zeit interviews sociologist Wolfgang Streeck about his intellectual influence on Sahra Wagenknecht’s political movement in Germany (discussed in Weekly Grounding #63). Streeck defends his egalitarian philosophical principles while at the same time offering a trenchant critique of mass immigration (one that is far more substantive than the current GOP electoral approach in the United States).

Streeck’s comments on democracy are particularly significant: “The crisis of the German political system is undeniable, and it’s not just a German phenomenon but can be observed in all Western capitalist societies: the collapse of the centre, the decline of social democracy, and the emergence of new parties that represent interests and values that previously had no place in the established party spectrum. This is usually described as a process of decay, at least from the perspective of the old parties, which might see it that way. But you could also describe it as a process of democratic renewal, if you understand democracy as an institution that gives space to the diverse experiences of citizens, allowing them to articulate and bring these experiences into politics. Many of these new parties are indeed very unsympathetic — Trump, for example, and similar ones in Holland, Italy, France. But if you understand democracy as the opportunity to vote out failed political elites, then you can still concede: yes, democracy exists for this kind of articulation of the will of the voters.”

“Dr. Jill Stein & Dr. Butch Ware On Green Party Policies, Trump Vs Kamala, Pathway To Victory”

Green Party presidential and vice presidential candidates, Jill Stein and Butch Ware, appear on The Breakfast Club. Whatever your views are on the Green Party, Stein and Ware contribute greatly to public discourse by making opposition to Israel’s genocidal war on Palestine the central issue in their campaign. Even more striking, though, is the behavior of one of the show’s hosts, Angela Rye, whose self-righteous and bad faith identity politicking made this episode go viral. The video is worth watching in full.

”To the Israeli Soldier Who Murdered Aysenur Ezgi Eygi”

writes a letter to the Israeli soldier who killed Turkish-American activist Aysenur Ezgi Eygi in the West Bank: “You were the last person to see Aysenur alive. You were the first person to see her dead. This is you now. And now no one can reach you. You are death’s angel. You are numb and cold. But, I suspect, this will not last. I covered war for a long time. I know, even if you do not, the next chapter of your life. I know what happens when you leave the embrace of the military, when you are no longer a cog in these factories of death. I know the hell you are about to enter.”Hedges continues: “The worst trauma from war is not what you saw. It is not what you experienced. The worst trauma is what you did. They have names for it. Moral injury. Perpetrator Induced Traumatic Stress. But that seems tepid given the hot, burning coals of rage, the night terrors, the despair. Those around you know something is terribly, terribly wrong. They fear your darkness. But you do not let them into your labyrinth of pain. And then, one day, you reach out for love. Love is the opposite of war. War is about smut. It is about pornography. It is about turning other human beings into objects, maybe sexual objects, but I also mean this literally, for war turns people into corpses. Corpses are the end product of war, what comes off its assembly line. So, you will want love, but the angel of death has made a Faustian bargain. It is this. It is the hell of not being able to love. You will carry this death inside you for the rest of your life. It corrodes your soul. Yes. We have souls. You sold yours. And the cost is very, very high. It means that what you want, what you most desperately need in life, you cannot attain.”

“Philosophy of the People”

writes a fascinating history of philosophy in the mid-nineteenth century American Midwest: “The Platonists of Illinois were centred around Hiram Kinnaird Jones of Jacksonville. The Hegelians of the St Louis Philosophical Society, meanwhile, were led by Heinrich Conrad (‘Henry Clay’) Brokmeyer and William Torrey Harris. These were movements of amateurs in the fullest and best sense: their ranks were composed of non-professional students of philosophy – lawyers, doctors, schoolteachers, factory workers and housewives – motivated by personal edification and the earnest pursuit of truth rather than professional achievement or status-acquisition. They conducted their activity against the backdrop of a country reeling from a bloody civil war, tenuously unified and engaged in an energetic campaign of westward expansion and industrialisation. The very intelligibility of their world had been thrown into question, and these readers and thinkers on the prairie found help in the great minds of the past. ‘The time,’ writes Denton J Snider, a member of the St Louis circle, ‘was calling loudly for First Principles’ – and, for their readers, Plato and Hegel offered paths toward them.”Of one of these philosophers, he writes: “The few worldly possessions that adorn the cabin of a St Louis ironworker: the wisdom, from worlds both ancient and modern, of ‘those who have made man’s life human.’ Labour provides the means of satisfying the hunger of the body; reading and thinking, the hunger of the soul. But a good life can be formed only in the unity of these two essential activities: man does not live on bread alone, nor can he live without it.”

Keegin perceptively observes that “In the past century or so, the market power and cultural influence of US colleges and universities has greatly increased, driven by the post-Second World War expansion of university education in the wake of the GI bill. As a consequence, the vibrant pluralism of the philosophic way of life has more or less flattened into a single option: that of the university scholar, whose credibility depends upon institutional affiliation. Before this radical transformation of US education, and the monopolisation of intellectual life by the university industry that followed in its wake, philosophy was understood to be – like all other pursuits of the mind and heart – a vocation with a professional expression, rather than the other way round.”

“Also Waiting for Godot.”

Speaking of labor,

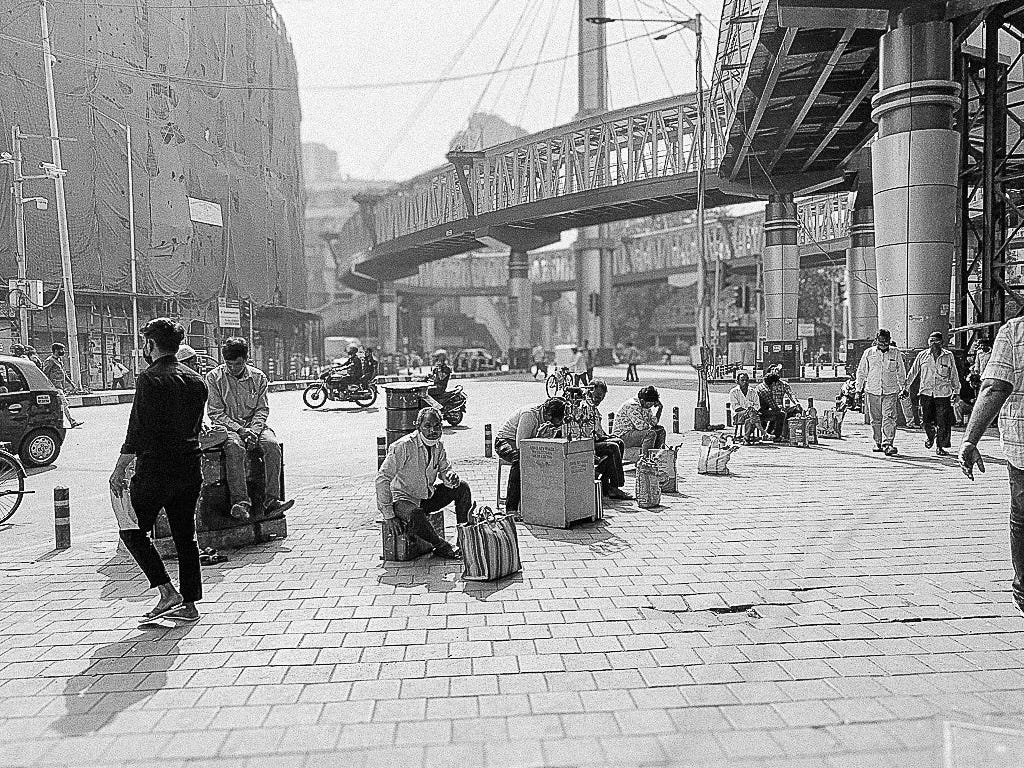

offers an incredible photo essay on daily wage laborers in Mumbai, India.By way of introduction, he writes: “The largest employer in India is not Bharatbhai Sarkar, the Railways, or any of our current oligarchs. It’s the streets of India, where people help each other through time-tested informal networks. Every major crossroads, naka, chowk, mukku, or X road in our cities and small towns is home to one such network that provides daily employment to millions of Indians, one or two generations away from caste-enforced agricultural labour or trade in the hinterland, now building our cities or offering cheap labour to factories. In the last century, which ended with the death of labour, they would’ve had a little or some voice. In the current century, they are invisible, like cycles and pedestrians. And once you notice them, you cannot unsee the thousands you will find at major squares, railway stations, gates of industrial estates, and almost everywhere, waiting for work every morning. If they do not find work that day, they return home hungry.”

Here are a few of the photos—check out the link to see them all.

What grounded your thinking this week? Feel free to share in the comments.

Thank you, Vincent!