Ever catch a falling star?

Ain’t no stopping ’til it’s in the ground

Everybody is a star

One big circle goin’ round and round

—Sly and the Family Stone, “Everybody Is a Star”

America’s history, her aspirations, her peculiar triumphs, her even more peculiar defeats, and her position in the world—yesterday and today—are all so profoundly and stubbornly unique that the very word “America” remains a new, almost completely undefined and extremely controversial proper noun. No one in the world seems to know exactly what it describes, not even we motley millions who call ourselves Americans.

—James Baldwin, “The Discovery of What it Means to Be an American”

These words, penned by James Baldwin in 1959, speak to the complexity of the American condition. Despite this complexity, many influential thinkers—American and otherwise—are intent on identifying what they call “the average American.”

Take Elon Musk. In his recent Oval Office appearance with Donald Trump, Musk spoke exuberantly about how his overhaul of government spending would be a boon for “the average American.” Elsewhere, Musk critic

recently invoked the idea of “the average American” to explain why voters rejected identity politics in the 2024 election. These are just two of many examples that demonstrate how this phrase is used across the political spectrum. “The average American” is never defined, but we are expected to know exactly who he or she is.I want to suggest that “the average American” does not exist.

Averages and Americans

Allow me to begin on a philosophical note.

To trade in the discourse of averages is itself a dubious enterprise. Averages, by definition, do not have a concrete existence. Instead, they are arrived at through a process of abstraction that reduces a complex array of information to one ostensibly representative number or type. In a strictly mathematical scenario this can be useful, but it is a much less straightforward operation when the proverbial “data points” involved are human beings. While we can agree from a purely quantitative understanding of numbers that the average of 7, 2, and 3 is 4, the “average” of Tom, Dick, and Harry is much less clear. Indeed, finding the “average” of human beings is, on its face, absurd.

The confusion is even greater when we add “American” to the mix. Now we are not only talking about people in the abstract, but people who belong to a country that is, as Baldwin put it, “so profoundly and stubbornly unique” that it threatens to defy definition. If it is this challenging to define America in particular, then defining “the average American” becomes even more difficult than the already fraught endeavor of averaging out human beings in general.

Nonetheless, everyone from right-wing progressives like Musk to disgruntled leftist academics like Liu seem to believe that “the average American” can be identified and known. I find it interesting that we rarely, if ever, hear the “average American” using this term to describe himself. More often than not, it comes from elite quarters and seems to be used colloquially to refer to people who are not elite. Even when the elites in question purport to advance a non-elite agenda (as both Musk and Liu surely would, for different reasons), there is a uniquely elite self-satisfaction in identifying—and, therefore, purportedly knowing—“the average American.”

“The average American” reveals itself as an empty signifier waiting to be filled by the desires of those who choose to use it. In Musk’s case, “the average American” is someone who will be served by the DOGE agenda whether she realizes it or not. For Liu, “the average American” is a populist voter who rejects elite cultural progressivism. For someone else using the term it could mean something entirely different. The point is that the complex world of averages and Americans can be simplified and brought under control with this elegant and malleable phrase. The price, however, is the construction of an artificial abstraction bereft of concrete existence.

The Reign of Quantity in the United States

In his 1945 book, The Reign of Quantity and the Signs of the Times, philosopher René Guénon argues that the mentality of the modern world is fundamentally characterized by “the tendency to bring everything down to an exclusively quantitative point of view…” Guénon continues:

This tendency is most marked in the “scientific” conceptions of recent centuries; but it is almost as conspicuous in other domains, notably in that of social organization—so much so that…our period could almost be defined as being essentially and primarily the “reign of quantity.”

The “reign of quantity” has become so entrenched that almost all contemporary political camps in the United States take it as a given. Elon Musk defines political benefit for “the average American” in purely quantitative terms: deficits decreased, taxes cut, productive units increased. For Catherine Liu, “the average American” rejects identity politics because it is too qualitative—too preoccupied with essences, identities, and ideals. She advocates a return to “bread and butter” politics grounded in the “materialist” worldview of the pre-woke left. What unites Musk and Liu’s otherwise divergent perspectives is their quantitative understanding of politics in terms of material interest, an understanding that philosopher Hannah Arendt and others have described as “animal politics.”

I happen to agree with much of Liu’s scathing critique of radical liberal identity politics articulated in her recent interview with

from which the above quotes are drawn. It is no secret that I am much less sympathetic to Musk. That said, the two are tied together by their “quantitative point of view” on politics. In this sense it is no coincidence that neither hesitates to deploy the cliché of “the average American.” When politics is understood chiefly in terms of quantity, averaging out human beings is the logical conclusion.America does not need yet another version of the animal politics that dominates during the reign of quantity. What we need today is a human politics or, perhaps more precisely, a politics of the human being. This politics would recognize—and take as its starting point—the irreducible complexity of the human being and, by extension, be naturally inclined to address the complexity of the American condition that James Baldwin speaks to the epigraph of this essay. The inverse is also true: the complexity of the American condition brings into sharp relief the complexity of the human condition. In another essay, Baldwin offers a striking account of the human being, an account which can provide the foundation for a truly human politics against the rein of quantity:

[T]hat battered word, truth,…confronts one immediately with a series of riddles and has, moreover, since so many gospels are preached, the unfortunate tendency to make one belligerent. Let us say, then, that truth, as used here, is meant to imply a devotion to the human being, his freedom and fulfillment; freedom which cannot be legislated, fulfillment which cannot be charted. This is the prime concern, the frame of reference; it is not to be confused with a devotion to Humanity which is too easily equated with a devotion to a Cause; and Causes, as we know, are notoriously bloodthirsty. We have, as it seems to me, in this most mechanical and interlocking of civilizations, attempted to lop this creature down to the status of a time-saving invention. He is not, after all, merely a member of a Society or a Group or a deplorable conundrum to be explained by Science. He is—and how old-fashioned the words sound!—something more than that, something resolutely indefinable, unpredictable. In overlooking, denying, evading his complexity—which is nothing more than the disquieting complexity of ourselves—we are diminished and we perish; only within this web of ambiguity, paradox, this hunger, danger, darkness, can we find at once ourselves and the power that will free us from ourselves.

Everyday People

Some may respond to the case presented in this essay with the rejoinder that “the average American” is simply a heuristic, a practical (if imperfect) way of understanding and acting upon political reality. I have no problem with heuristics, but I do have a problem with heuristics that implicitly reinforce the reign of quantity. Fortunately, there are other phrases that are much better than “the average American” at serving a heuristic purpose without reducing political subjects to quantified objects.

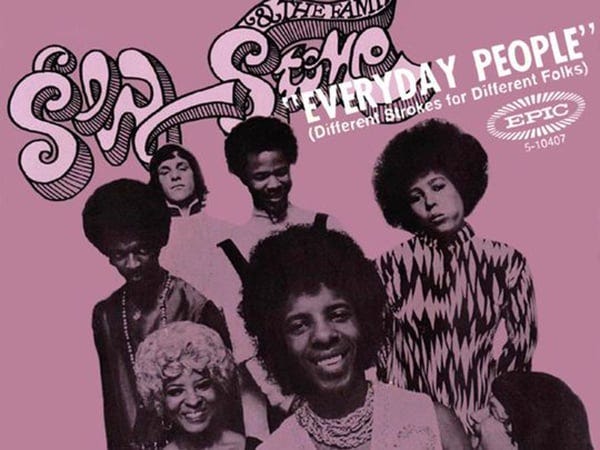

We need look (and listen) no further than Sly and the Family Stone, the Bay Area funk and soup group that defied—by its very eccentric and eclectic presence—any conception of “the average American.” In their 1968 hit single, “Everyday People,” the group puts forth a conception of American unity across difference that does not reduce anyone to an “average.” The song’s refrain, “I am everyday people,” suggests a complex understanding of the relationship between the individual and the collective. Rather than collapse the individual into the collective concept of “the average American,” this unconventional grammatical construction puts the “I” in intimate relationship with the “we,” presenting a revolutionary perspective on the perennial problem of the one and the many.

In 1969, the band released another single, entitled “Everybody Is a Star.” The repetition of the “every-” prefix indicates an intentional attention to each human being, rather than a hypothetical “average American.” Everyday people are not just unique individuals but are also the very stars who illuminate the profoundly unique American cosmos:

Everybody is a star

I can feel it when you shine on me

I love you for who you are

Not the one you feel you need to be

Elon Musk—a South African who displays his ignorance of America on a daily basis—probably wouldn’t see enough value in the song to even consider its philosophical implications. Liu traces the origins of contemporary identity politics back to the 1968 generation and the hippie counterculture, so would likely dismiss Sly and the Family Stone as the soundtrack to these regrettable developments.

I believe that there is something in the band’s work that speaks directly, and deeply, to our present predicament. In “Everyday People” and “Everybody Is a Star,” we find the seeds of a qualitative alternative to the shibboleth of “the average American” that emanates from the quantitative view of politics. It is this alternative qualitative conception of the human being that America needs today.

There is no “average American.” Everybody is a star.

Interesting that you quoted The Reign of Quantity and the Signs of the Times. He also criticizes egalitarianism and democracy in that book, which he views as examples of the reign of quantity, because they disregard the qualitative features of persons that result in hierarchical distinctions.

This answers my earlier question: what do Americans think.