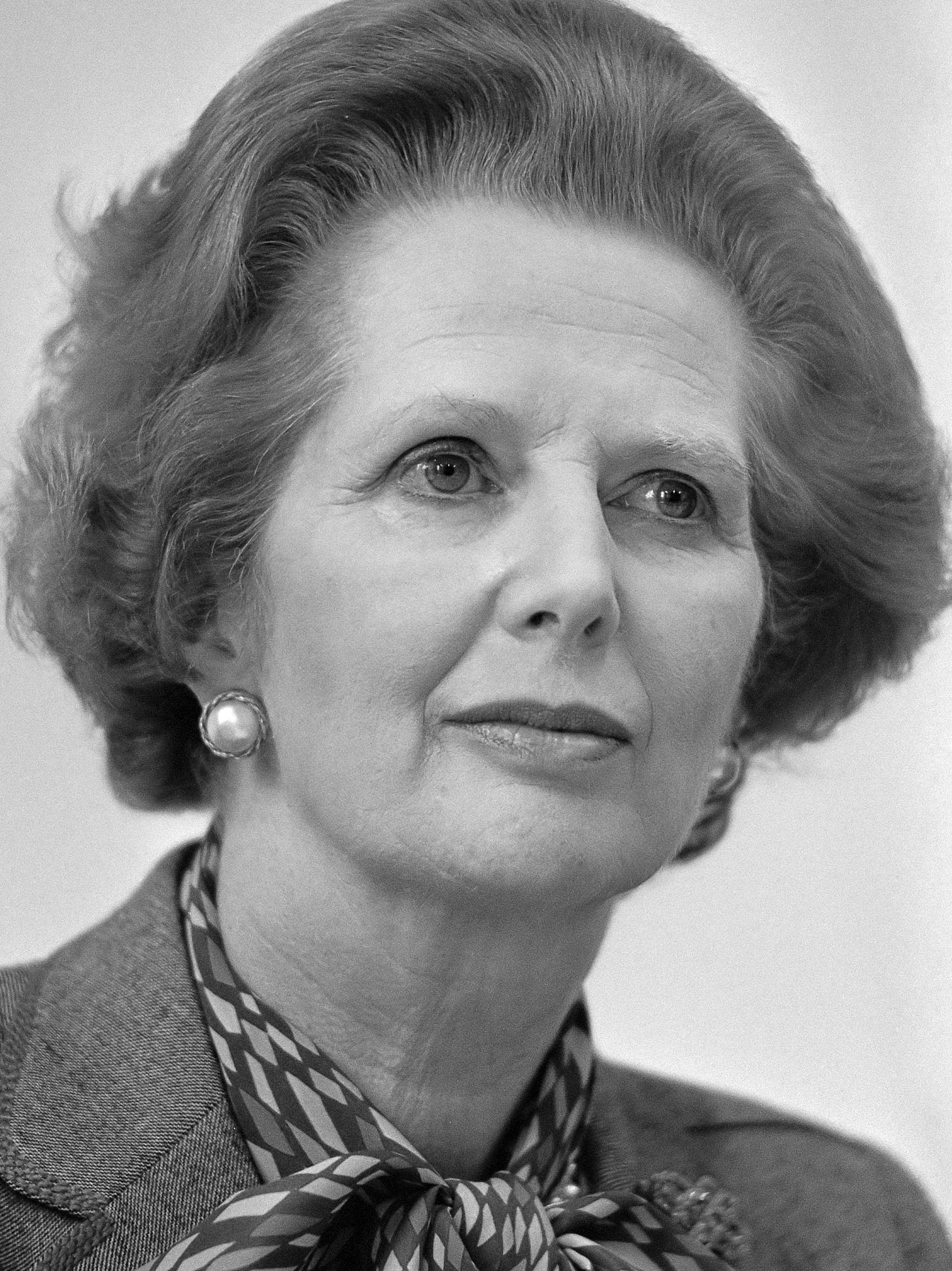

In 2002, Labour Party spokesman, Peter Mandelson, declared that “We are all Thatcherites now.” Mandelson’s declaration came five years after Tony Blair’s landslide electoral victory in 1997, which cemented his rebranding of the British Labour Party as “New Labour.” Blair’s New Labour vision for Britain substituted aspirational middle class politics for working class organization and promoted the dominance of finance capital over the country’s industrial base. Most of all, New Labour sang the praises of globalization.

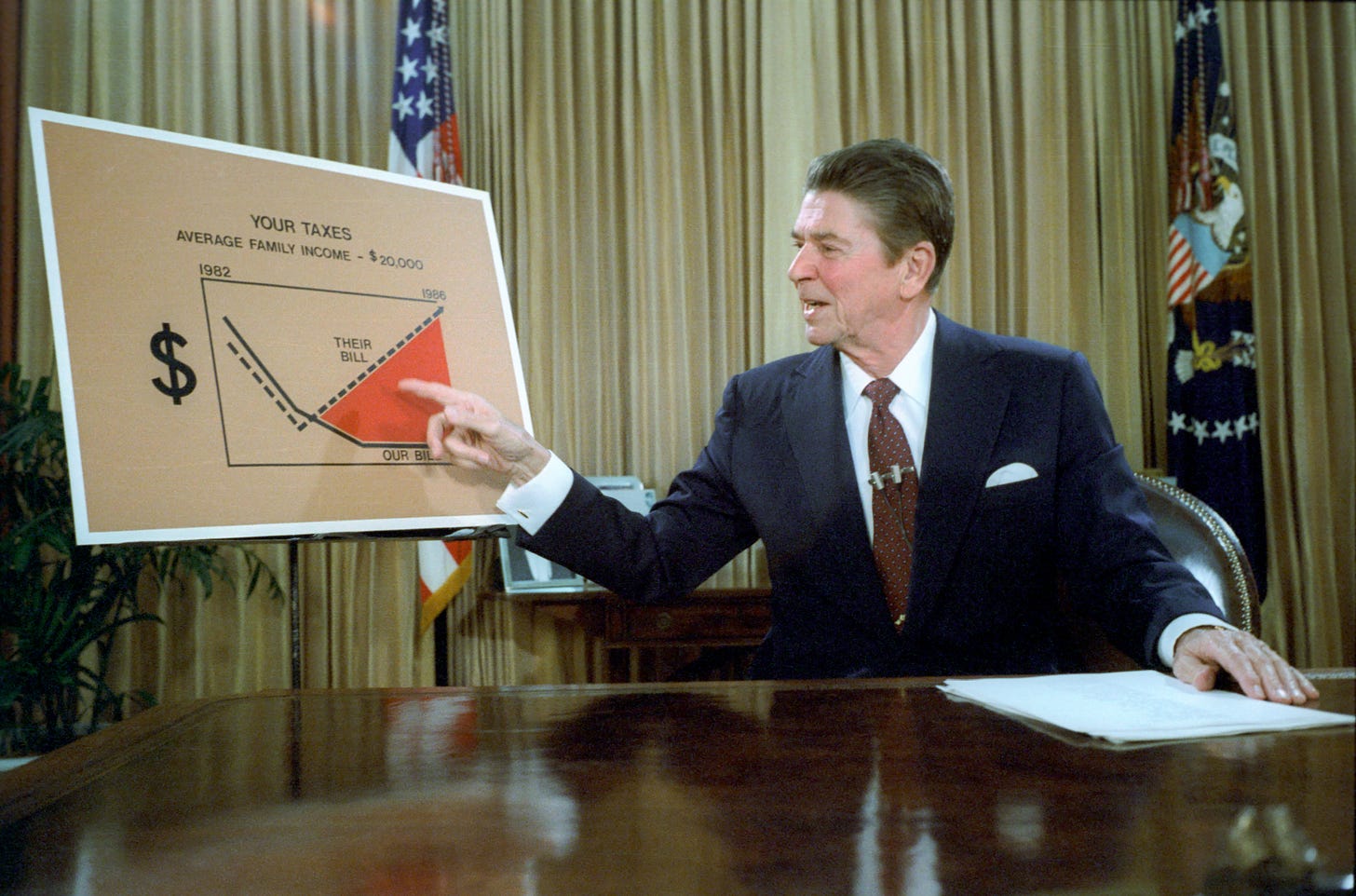

Mandelson’s statemenet captured the ruling class zeitgeist of the United States and United Kingdom in the early 2000s. Emboldened by the collapse of the Soviet Union a decade earlier, both countries embraced unfettered economic globalization as a historical inevitability and necessity. Though this ideology was, at first, most closely associated with the 1980s conservatism of Ronald Reagan in the U.S. and Margaret Thatcher in the U.K., by the turn of the century the American Democratic Party and the British Labour Party had also come to accept neoliberal orthodoxy. “We are all Thatcherites Now.”

In the United States, neoliberalism was the dominant economic paradigm of subsequent Republican and Democratic administrations up through Barack Obama’s two terms as president from 2009 to 2016. Since 2016, however, the upper echelons of American politics have witnessed a radical transformation in economic ideology and policy. The campaign and presidency of Donald Trump was a catalyst for a broader turn against neoliberalism in American presidential politics, which has continued under Joe Biden.

My argument in this piece is twofold: First, rather than a wholesale rejection of the left, Trumpism can be more productively understood as the ideological mainstreaming of the late-1990s and early-2000s anti-globalization movement. Second, contrary to popular conceptions of Joe Biden and Donald Trump as diametrically opposed ideological and political figures, the Biden administration has accepted and, in some cases, furthered Trumpian ideology and policy.

While Trump himself has recently abandoned some elements of his anti-globalization program, Trumpism as a broader political-economic-ideological framework has come to transcend the figure of Trump himself. In this sense, we are all Trumpians now.

Trickle-Up Ideology: Trumpism as the Ideological Triumph of the Anti-Globalization Movement

One of the catchphrases of the neoliberal revolution was “trickle-down economics.” According to this dictum, economic policies designed to benefit the rich would eventually “trickle down” to also benefit the poor through increased economic growth. While tickle-down economics turned out to be a lie, its failure produced a strong resistance to neoliberalism among wide swathes of an increasingly angry public in the West in the form of the anti-globalization movement. Though many have consigned this broad coalition to the dustbin of history, it is precisely the ideology of the anti-globalization movement that eventually trickled up to the level of presidential politics and policy with the campaigns and administrations of Donald Trump and Joe Biden.

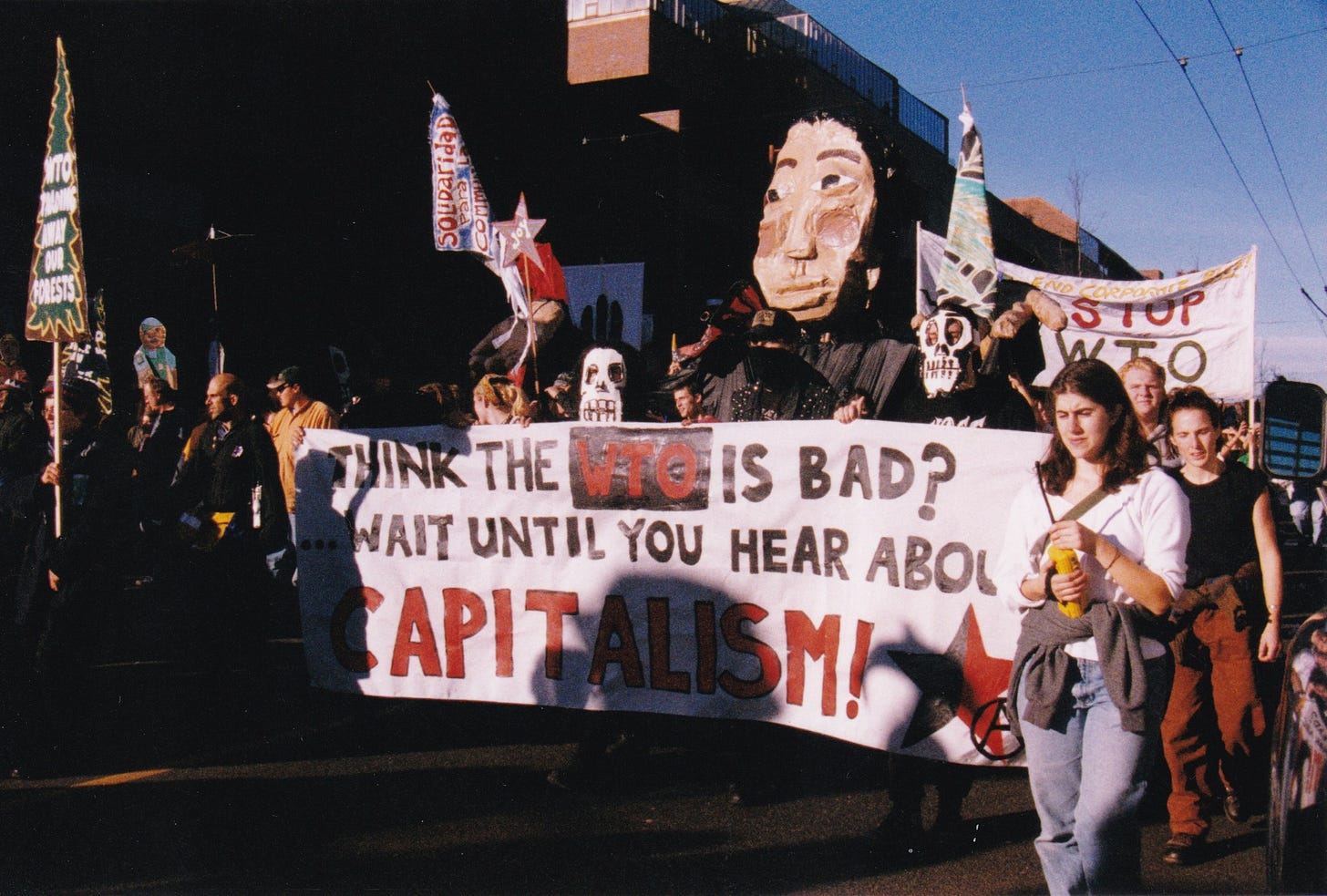

Legal scholar Amy Chua describes the anti-globalization movement that coalesced in response to neoliberal orthodoxy as “a host of strange bedfellows: American farmers and factory workers opposed to NAFTA, environmentalists, the AFL-CIO, human rights activists, Third World advocates, and sundry other groups that made up the protestors at Seattle, Davos, Genoa, and New York City.” While these strange bedfellows were not united by class location or cultural persuasion, the anti-globalist ideology that came to define their movement in the late-1990s and early-2000s transcended internal divisions.

Though there were elements of this movement linked to the political right, the anti-globalization movement was an overwhelmingly left-wing political phenomenon. This was no more evident than during the historic 1999 protests at the World Trade Organization (WTO) conference in Seattle, Washington. At the “Battle of Seattle,” masses of leftist activists linked opposition to free trade agreements with a critique of the capitalist system writ large. The activists clashed with a militarized police force, putting the anti-globalization movement on the political map as a serious force for the globalist ruling class to reckon with.

The anti-globalization movement had largely redirected its efforts toward opposing the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan in the mid-2000s. By the time of Obama’s election in 2008, many of its activists had aged out of the kind of direct action that had defined protests like the ones in Seattle. The Occupy Movement in 2011-12 was, in many ways, the last gasp of the anti-globalization movement in the United States.

The rise of a new generation of millennial leftists enamored with race, gender, and sexuality identity politics in a post-Occupy America helped produce economic populism’s rightward drift in the 2010s. In contrast with the public displays of direct action popularized by left-wing anti-globalization activists, the new face of resistance to neoliberalism began to be associated with the more subdued style of “American farmers and factory workers opposed to NAFTA” whom Chua identified as a part of the anti-globalization coalition in early 2000s. While there is nothing inherently right-wing about farmers and factory workers, the cultural excesses of elite leftist identity politics began to push these demographics to the right during Obama’s second term.

Central to Trump’s appeal to poor and working class voters was his anti-globalization campaign rhetoric.

observes that, during his 2016 presidential campaign, Trump “feuded incessantly with corporate America, telling a story about big business as part of the corrupt establishment trying to outsource jobs and replace American workers with cheap labor.” While it is commonplace in left-liberal circles to dismiss Trump’s rhetoric as empty right-wing populism, Stoller documents the multiple ways in which Trump followed through on his anti-globalization campaign messaging as president:Trump withdrew the U.S. from the Trans-Pacific Partnership, renegotiated NAFTA, and raised tariffs on Chinese imports. The press pretended that this stuff was mostly fake, but it wasn’t. For instance, the Trump administration blocked imports of lumber from a Peruvian exporter based on concerns over illegal harvesting, the first use of environmental standards in trade law ever by the U.S. government. As another example, there’s now a wave of Mexican labor organizing spurred by the labor provision in the new NAFTA.

Opposition to NAFTA, and, later, the Trans-Pacific Partnership (described by The Nation in 2012 as “NAFTA on Steroids”), were two central causes of the anti-globalization movement. It will stand as one of the many ironies of history that Donald Trump, a figure loathed by the veterans and heirs of the anti-globalization movement, did more than any president before him to disrupt the elite globalist consensus on so-called “free trade.”

Trumpian anti-globalization did not come out of nowhere. The anti-globalization movement itself deserves the bulk of the credit for raising the alarm about NAFTA and the TPP well before Trump came on the political scene. Trumpism, which in this sense can be understood as a reconfigured and rebranded form of anti-globalism, is an example of trickle-up ideology: The broad coalition of the anti-globalization movement was repressed by the neoliberal Clinton, Bush, and Obama administrations. Despite these concerted efforts to erase anti-globalization ideology, this movement finally made its well-deserved mark on the highest level of American politics in the form of Trumpism.

Bidenomics: The Logical Conclusion of Trumpism

The continuity between Trump’s anti-globalism and what has come to be known as “Bidenomics” is one of the most remarkable stories in American politics from the last several years. While Biden departed from many Trump administration lines on foreign policy and culture, Bidenomics has, paradoxically, represented the political victory of Trumpism in the sphere of economic policy.

Part and parcel of Trump’s attacks on free trade agreements was a call for the re-industrialization of the American economy. “It's a line that draws thunderous applause at Republican presidential candidate Donald Trump's campaign rallies, one that can sometimes even bring the crowd to its feet: Let's bring back America's lost manufacturing jobs,” NPR reported in 2016. Just last year, economist and New York Times columnist Paul Krugman wrote that “One central theme of Donald Trump’s 2016 campaign was a promise to bring manufacturing jobs back to the United States.”

While Trump’s efforts to re-shore production were less impactful than his broader challenge to the global free trade consensus, the Biden administration has done more than any other since the neoliberal revolution to re-industrialize the American economy. In other words, Bidenomics has picked up where Trumpism left off on the question of industrial policy.

In his 2023 essay, “The Left’s Foolish Attack on Bidenomics,” Justin Vassallo argues that “over the past three years, the Biden administration has critiqued neoliberalism in words…and in deeds.” He elaborates:

The centerpiece of the post-neoliberal turn among Democrats is industrial policy, as exemplified by the Inflation Reduction Act, the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act, and the CHIPS and Science Act. Taken together, these measures represent a significant step toward restoring domestic manufacturing, while combating regional inequalities and boosting worker power via higher pre-tax wages (as opposed to means-tested post-tax assistance to lower-income Americans).

Vassallo argues that, “Whatever the deficiencies of ‘Bidenomics,’ it has established national economic objectives beyond the order of anything seen since the end of the New Deal order.” What he fails to mention is that Donald Trump’s 2016 campaign and four years in office laid the political and ideological groundwork for Biden to actively pursue a post-neoliberal economic policy.

Trump attempted to promote re-industrialization “by slapping tariffs on many imports” and Biden has only expanded this policy. The New York Times reported this May that Biden’s steep tariff increases on Chinese goods “codify and escalate tariffs imposed by Mr. Trump [and] made clear that the United States has closed out a decades-long era that embraced trade with China and prized the gains of lower-cost products over the loss of geographically concentrated manufacturing jobs.”

Financial Times columnist Edward Luce sums up the political ramifications of this decisive policy shift: “The two great points of consensus in today’s US are that globalisation is toxic and that America is in a zero sum competition with China.” In a guest FT opinion piece entitled “The Trump-Biden Consensus on the Economy is Bad for Business,” director of economic policy at the American Enterprise Institute, Michael Strain, notes that both Trump and Biden “reject the broad consensus that largely governed economic policy in the decades before Trump’s 2016 election—one that is generally supportive of business and in favour of free enterprise.”

Despite Biden’s rhetoric about the existential threat posed by a second Trump presidency, he has arguably done more than Trump did to turn Trumpian dictums into bipartisan “points of consensus.” The Bidenomics framework of industrial policy, protectionism, and antitrust has reinforced rather than rebuffed Trumpism.

The Future of Trumpism Transcends Trump

I began writing this piece before the assassination attempt on Donald Trump at his Butler, Pennsylvania rally on Saturday. In light of this historic event, I had to reconsider the implications of my central argument that Trumpism transcends Trump. Is, as

claimed in the wake of the assassination attempt, Trumpism merely the expression of the “Christian fascist” desire for a “cult leader”? While there is undoubtedly a cult of personality surrounding Donald Trump among quarters of his base, the evidence indicates that Trumpism has much broader and deeper appeal than Trump as an individual.

Michael Lind perceptively observes that “however incoherent Trump may sometimes be, he has tapped into a worldview with certain coherent public policy positions.” Chief among these is an opposition to globalization. The anti-globalization movement is nearly three decades old, but it is only within the last decade that Trumpism put its agenda on the table in the upper echelons of the policy world. Rather than dam the trickle-up ideology of Trumpism, Biden’s presidency has further opened the floodgates. Anti-globalization is at the heart of Bidenomics and represents the practical instantiation of Trumpism in the sphere of economic policy.

Biden’s wars in Ukraine and Gaza have attempted to fortify globalist American imperialism against a post-globalization economic policy backdrop. Despite the Biden administration’s efforts to pursue these policy goals in tandem, the contradiction between them has only been thrown into sharper relief as American funding of the conflicts in Eastern Europe and the Middle East continues. The Biden administration’s frantic efforts to resuscitate a moribund global empire are increasingly unpopular with an electorate that wants an anti-globalization economic and foreign policy. Following in the footsteps of the left-coded anti-globalization movement, right-coded Trumpism calls for an end to neoliberal economic globalization and globalist forever wars.

Trump’s selection of J.D. Vance as his vice presidential running mate further strengthens the case for the ideological triumph of the anti-globalization movement.

notes that, “Since his election in 2022, the junior senator from Ohio has blazed an unorthodox path as a Republican on fundamental economic and foreign policy issues.” The Washington Post corroborates Fang’s analysis, reporting that “Vance has suggested a break with the Republican Party’s economic orthodoxy of the last several decades on a range of policy issues, including unions, antitrust, trade and taxes…” Vance has publicly expressed his support for Biden administration antitrust bulldog, Lina Khan, demonstrating the fundamental alignment of Bidenomics with Trumpism.While Biden won the battle of the 2020 presidential election, four years later it is Trump or, more accurately, Trumpism, that has won the war. Trumpism is no longer wedded to Trump as an individual personality; it has become a bipartisan electoral imperative for Republicans and Democrats alike. If Trump had been killed last weekend, Trumpism would have outlived him.

We are all Trumpians now.

Fascinating analysis, Vincent. I'll be linking to this in an upcoming piece on the '99 WTO protests in Seattle.

An interesting analysis, thank you.