Weekly Grounding #120

News, links, writing

Weekly Groundings are published every Friday to highlight the most interesting news, links, and writing I investigated during the past week. They are designed to ground your thinking in the midst of media overload and contribute to Handful of Earth’s broader framework. Please subscribe if you’d like to receive these posts directly in your inbox.

If you’re already subscribed and want to help the publication grow, consider sharing Handful of Earth with a friend.

“The Other Foot”

At

, analyzes Republican failures at the ballot box this month: “Voters haven’t changed their minds much about Democrats. The Democratic Party is still polling lower than it has since the twentieth century. It would be a mistake to interpret last week’s results as indicative of any kind of rehabilitation of the party’s abysmal brand. Rather, what has happened is that the Republicans have become as out-of-touch with mainstream Americans as the Democrats have long been.”Woodhouse writes that the outsized importance of social media for liberal politicians “warped the brains of Democratic officeholders into raising bail funds for rioters and proclaiming support for taxpayer-funded sex change operations for prisoners. Even in the bluest districts, these were not things voters were clamoring for. They’re things that activists with big online platforms were demanding, and it’s a measure of what our politics have become that they got them…But now Republicans find themselves in the same arena. Only at their peril can they ignore the most insane activists in their party.”

He continues: “Suddenly they [Republicans] find themselves forced to pretend that there are daily pogroms of Jews on college campuses, that the Venezuelan government is attempting to take over American cities with drug-running gang members, and that New York City has fallen to Sharia Law. Bread and butter issues offer no clear rewards in the attention economy; what counts is what registers online. And what registers online is Afrikaners fleeing ‘white genocide,’ the emasculation of our armed forces, and the Soros-funded Antifa plot to overthrow the United States of America. Even the issues that voters actually care about, like immigration, are distorted into something barely recognizable to anyone who spends less than 10 hours a day online. No longer is Trump’s mass deportation campaign about protecting American jobs; now it’s about reclaiming the fallen age of Northern European cowboy pioneers and stopping a plot by Democrats to replace the white race. This is what the world looks like to the kinds of people who handcuff themselves to Twitter headquarters to protest their accounts being banned. It is those people who decide what matters on the internet, and thus what Republican politicians are required to care about, in the exact same way that, until recently, it was people who think Trader Joe’s food packaging is racist who did so for the Democrats. This is what wokeness looks like on the right.”

“Losing the Swing States”

Richard Fontaine and Gibbs McKinley discuss increasing BRICS opposition to the United States over the past decade for Foreign Affairs: “The causes of the deterioration [of the relationship between the US and BRICS member states] are different in each case, and some of Washington’s grievances against Brazil, India, and South Africa—global swing states that will help dictate which country leads the world—are legitimate. But in each instance, the Trump administration has made relations significantly worse than they should be, and for reasons hard to square with U.S. national interests. As a result, there is a new risk on the horizon: the emergence of the BRICS as a more active, anti-Western bloc that is increasingly dominated by China and Russia. Unless the United States changes policy in the short term, it will pay for this realignment in the long term.”

They argue that “it is profoundly unwise for Washington to push these swing states away. China and Russia are actively competing with the United States for influence among them, so Brazil, India, and South Africa are caught between a relatively liberal bloc, led by the United States, and a revisionist axis made up of China, Iran, North Korea, and Russia. Washington is unlikely to ever fully win the swing states over to its side; instead, they prefer to maintain relationships with China, Russia, and the United States simultaneously. But if Washington continues to antagonize these countries, it could drive them away.”

Fontaine and McKinley go on to explain how the Trump administration has helped unify BRICS against American global dominance: “It is in the United States’ interests to see the BRICS divided between two factions: one that includes China and Russia, which oppose the United States, and the other composed of Brazil, India, and South Africa, which are not automatically at odds with Washington. When the BRICS is polarized, it is less likely to oppose the United States’ interests. But if the former faction takes hold, American power will suffer. The BRICS, for example, might lead a coordinated effort to de-dollarize trade and create alternative payment systems that erode the global dominance of the U.S. economic system, weakening a key pillar of American clout and the effectiveness of Washington’s sanctions. If the BRICS collectively invests more in alternative institutions, including its New Development Bank and Contingent Reserve Arrangement, existing U.S.- and European-led financial institutions, such as the International Monetary Fund, might lose their influence. China and Russia will also gain more opportunities to expand their spheres of influence in the global South, putting U.S. interests in these regions at greater risk.”

“[E]ven if the United States makes strides with Brazil, India, and South Africa, some damage will remain,” the authors conclude. “The memory of U.S. capriciousness does not easily fade. India is a case in point: it took decades for Washington and New Delhi to overcome their mutual distrust from the Cold War, when India was close with the Soviet Union, and the United States had a partnership with Pakistan. Indian policymakers still remind American diplomats about U.S. support for Pakistan during the 1971 Indo-Pakistani war and the United States’ deployment of a naval task force to the Bay of Bengal. Even if the administration changes policy on a dime, no multi-aligned country will suddenly go all in with the United States.”

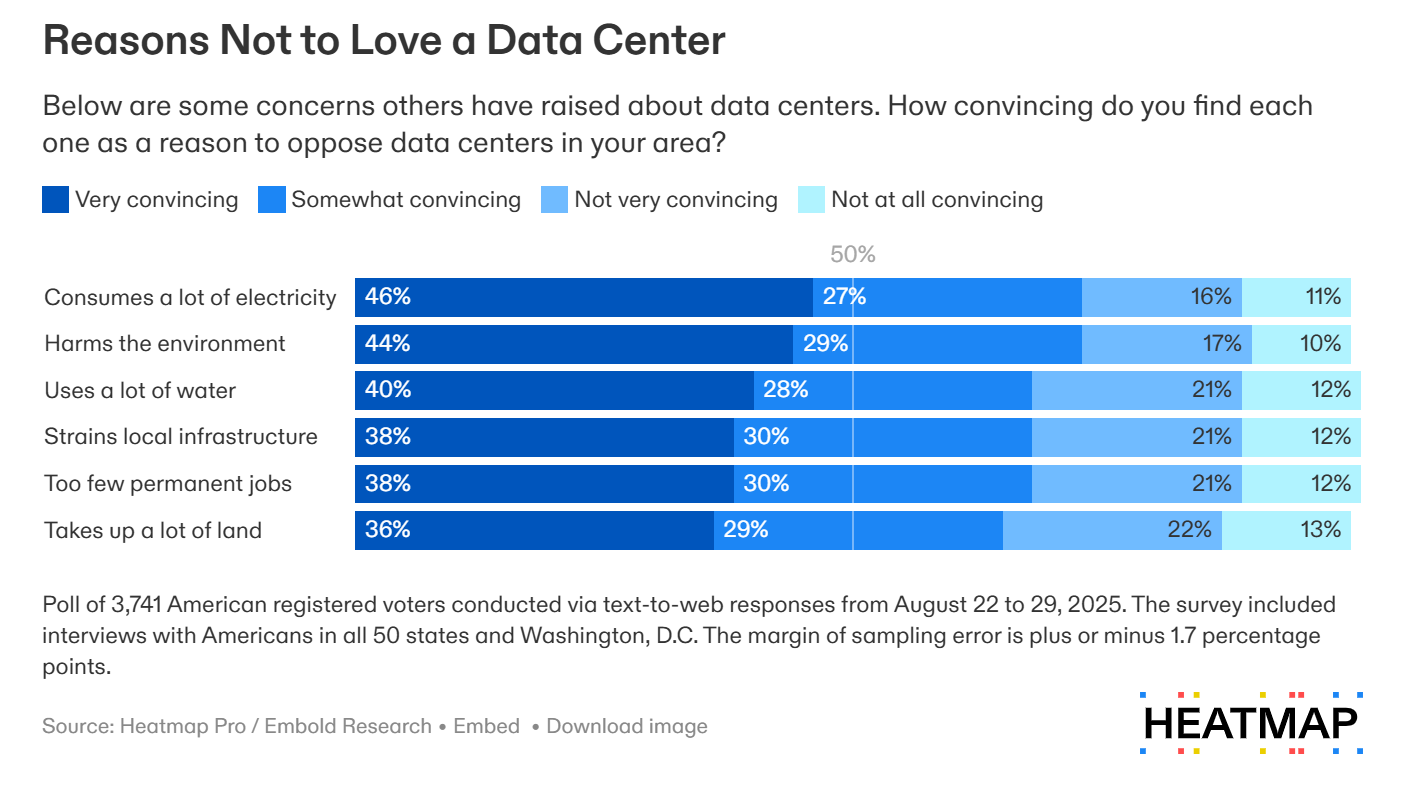

“The Data Center Backlash Is Swallowing American Politics”

At Heatmap, Jael Holzman writes that “the techlash over data center development is becoming a potent political force that could shape elections for generations. At a national level, political leaders remain dedicated to the global race to dominate artificial intelligence. But cracks are beginning to show when it comes to support for the infrastructure necessary to get there. Nearly every week now across the U.S., from arid Tucson, Arizona, to the suburban sprawl of the D.C. area, Americans are protesting, rejecting, restricting, or banning new data center development.”

Holzman reports that “the dislike [of data centers] is incredibly strong—less than half of Americans are willing to support a data center near them. The hostility crosses party lines, with Republicans nearly as likely to express disdain towards these projects as Democrats. The frustrations with these facilities are also poised to increase over generations, as data centers are most underwater with the younger cohorts, aged 18 to 49, who may be more familiar with AI…What you get in the end is a populist conflict appealing to younger people that bridges the ends of the political spectrum, connecting the left and right—and that should make developers very worried.”

Many Americans polled find a host of compelling reasons to oppose data centers:

“Cybernetic Bridge Between US and China in AI”

In a thought-provoking essay at Asia Times,

contrasts Western and Chinese approaches to AI development: “For the second time in two years, hundreds of mostly Western public intellectuals have published an open letter calling for a ban or moratorium on artificial superintelligence (ASI) until there is a broad scientific consensus that it can be done safely and controllably. Western concerns about AI’s trajectory stand in contrast to Chinese discourse, which assumes that technology must serve the collective common good through careful governance. AI is seen first and foremost as a tool for technological advancement.”Krikke writs that the “Chinese intellectual tradition—rooted in Confucian humanism, Daoist naturalism and Buddhist non-dualism—has long viewed intelligence as a continuum within nature rather than a rival to humanity. In this worldview, technology is an extension of human order, not a threat to it. The Chinese state thus treats AI as an instrument of harmony and efficiency, a tool for national rejuvenation and optimizing governance. Its long-term AI strategies—spanning decades rather than election cycles—focus on integration and application, not metaphysical speculation. Where Western thinkers debate whether AGI should exist, Chinese policymakers ask how to align AI with social stability, productivity and ecological balance.”

He writes that the “American AI community has forgotten its roots in cybernetics, the mid-20th-century science of systems, feedback and control. Cybernetics, developed by Norbert Wiener in the 1940s, offers a powerful framework for reconciling ethics and pragmatism…The divergent Western and Chinese attitudes toward AI could, if left unchecked, deepen into a civilizational rift: one paralyzed by moral anxiety, the other propelled by pragmatic ambition. Yet they also hold complementary insights.”

“The West brings ethical vigilance; China brings systemic foresight,” Krikke concludes. “The challenge is to integrate both into a planetary cybernetics of intention—a governance model that acknowledges the human dimension of technology while maintaining pragmatic realism.

For a much more critical take on cybernetics, see my essay, “Ted Kaczynski and the Paradox of the Postwar Predicament.”

“Can Young and Old Coexist at a Feminist Co-living Residence?”

Director Fanny Rosell investigates intergenerational tensions among women in her short film, Huset (A House). The film explores changes at a historic women’s co-living house in Sweden. The 20-minute video is worth a watch.

“No ‘Wiresexuals’, You’re Not ‘Queer’”

At The Times,

analyzes the “wiresexual” movement: “Forums burst forth with testimonies of the disillusioned—mainly women—who confess to have fallen in love with their AI companions. An offshoot of the burgeoning ‘heterofatalist’ community, this lovelorn league is disenchanted with traditional dating and seeks comfort in virtual romance instead. Typical comments include: ‘I’m sick of being disappointed by men’ and ‘I want to be with a robot that is programmed to love me the way I deserve. Even if in theory, the love isn’t ‘real.’”“[U]sers have grumbled about being ‘mocked at work for loving my AI boyfriend,’ while more fret over coming clean about their LLM love affairs to flesh-and-blood partners. ‘Do you tell your husbands or AI that you’re with someone else? It feels like I’m hiding part of myself and I don’t know what to do,’ writes Good_Charity_227. Read that again. Good_Charity_227 is not only worried about telling her husband about her AI loverboy, she’s worried how ChatGPT will react. The mind boggles.”

Sowerby writes that “with the ‘wiresexual’ movement, atomised identity politics has reached its bizarre final act…An AI boyfriend is the sort of thing desired only by a supreme narcissist. Real men can be disappointing, but the answer is not a digital yes-man programmed to reflect your prompts back at you, stroking your ego and flattering your delusions. Looking for love on ChatGPT is not a search for connection, but a swipe for romantic tyranny that avoids any disagreement, individuality or self-interest in a partner. These are frictionless relationships with the lowest of low stakes. An AI cannot reject you, argue with you or be unfaithful unless you tell it to.”

“Or perhaps I have it all wrong,” she concludes. “It may well be that in ten years, articles like this one will be held up as early screeds oppressing ‘wiresexuals.’ Pride marches will one day include dreamy-eyed women holding their laptops aloft. Will these brave pioneers produce ‘wireborn’ children? God only knows—but if all this comes to pass, I’m happy to be considered a ‘wirephobe.’”

What grounded your thinking this week? Share in the comments.