Why Free Speech? (Part 2)

Five alternative arguments for freedom of speech

In “Why Free Speech?” I reflected on the contradictions within the classical liberal justification for freedom of speech. That essay was inspired by my attendance at the Freedom for Individual Rights and Expression conference in Philadelphia this summer and prompted broader reflections on my personal political trajectory as it pertains to the question of free speech. Besides my critique of the classical liberal justification for free speech, I discussed philosopher Akeel Bilgrami’s alternative argument for free speech and hinted at another justification for free speech implied by Mario Savio’s famous speech during the Berkeley Free Speech Movement of the 1960s.

Despite these gestures toward constructive alternative arguments, after publishing the essay, I still felt uncertain in my own philosophical case for freedom of speech. While I hold the conviction that free speech is both ethically and politically essential, my ability to articulate an argument for why this is the case lags behind my intuitive response to the problem. I owed myself and my audience a Part 2.

Part 2 is an attempt to further elaborate alternative justifications for liberty of speech. I offer five distinct arguments. They may overlap, but all of them, I believe, stand alone as distinct justifications for freedom of speech. What follows is an open-ended effort to grapple in greater depth with the question that motivated the first part of this essay: Why free speech?

This query inspired a number of related questions that have preoccupied me since the FIRE conference and after publishing Part 1: What is the best argument for free speech? Is it possible to justify free speech outside the framework of liberalism? How can the free speech movement be revived to resonate with a broad section of the population? It is these kinds of questions which animate the five arguments for free speech explored below:

The Argument from Creativity and Diversity

The Argument from Dialectics

The Argument from Just Deserts

The Argument from Religious Humanism

The Argument from Duty

Let me explore each of these in turn.

#1: The Argument from Creativity and Diversity

This is Akeel Bilgrami’s argument, which I will briefly recap here (for a more detailed explanation, please see Part 1). Because his focus is on academic freedom, Bilgrami is principally concerned with why university administrators and scholars should permit and even encourage intellectual frameworks different from their own. But Bilgrami’s argument can be extrapolated to the issue of free speech more broadly. He writes:

We should allow alternative frameworks not because we have some generalized doubt that we ourselves might be holding false views. We should allow alternative frameworks for quite different kind of reasons…having to do with the fact that if we allow for frameworks of investigation other than our own, we make for an attractively diverse intellectual ethos and in doing so allow the creativity of different sorts of people and minds to flower.

Bilgrami proposes a value-laden rather than value-neutral justification for free speech. His argument suggests that free speech is not a precondition for all other values; instead, it must be supported by values external to itself, such as creativity and diversity.

Bilgrami’s position rejects the fallibilist doctrine of classical liberalism as the foundation of a persuasive argument for free speech. As an alternative, he suggests that we can be reasonably confident in the correctness of our own views and, at the same time, still value freedom of speech in the name of a broader conception of human flourishing. A wide range of people can only flourish, according to Bilgrami, if they are permitted to freely express their perspectives without censorship.

#2: The Argument from Dialectics

A second, related justification for free speech hearkens back to ideas from ancient philosophy. We might conceive of this argument as an extension of the argument for the Socratic method. Underlying the Socratic method is the conviction that truth can only be arrived at through dialogue. Bilgrami himself invokes this tradition of thought in an interview, where he proposes the value of “engagement” as a philosophical basis for free speech.

This argument from dialectics contends that truth is fundamentally about relationships between human beings. No one of us can know the truth in isolation because we depend on others to point out our internal contradictions and errors. As such, we need freedom of speech not simply because we may be wrong, but because we are more likely to be right when working together. A version of this idea can also be found in the Book of Proverbs of the Old Testament: “As iron sharpens iron, so one person sharpens another.”

This is an elegant argument for free speech. Where it runs into trouble is in the practical difficulties of achieving good faith dialogue in the present hyper-polarized political climate. Branko Milanovic has addressed this problem in his pithy piece, “On General Futility of Political Discussions with People,” in which he concludes that:

if one believes in a certain point of view and yet has a limited amount of mental energy, it is entirely wasteful to use it in trying to convince others in direct discussions. It is much more effective to write and read and listen than to have Socratic or any other dialogues. They, I think, lead nowhere.

Given my own experience with political discussions, I largely agree with Milanovic that direct political dialogue often deepens preexisting divisions rather than leading to a higher dialectical synthesis of ostensibly oppositional positions. Nevertheless, the argument for freedom of speech from dialectics is still compelling, at least for written speech and receptive listening. Moreover, it has much deeper historical roots than the classical liberal argument so often invoked as the only “universal” case for liberty of speech.

#3: The Argument from Just Deserts

As I have been reflecting on justifications for free speech, one alternative argument is something that I will call the argument from just deserts. What do I mean? This argument moves beyond the level of the individual or the small group toward a broader conception of social life. The argument from just deserts is less intuitive than arguments #1 and #2, so, for clarity’s sake, allow me to state it more formally:

Premise A: Disagreements within society are a product of social contradictions within that society.

Premise B: As members of society, we are all—to a greater or lesser extent—implicated in these social contradictions.

Conclusion: Therefore, we should not censor the views of those with whom we disagree, not because we think they might be correct, but because we have an obligation to face the consequences of the social contradictions which we have played a part—however small—in creating.

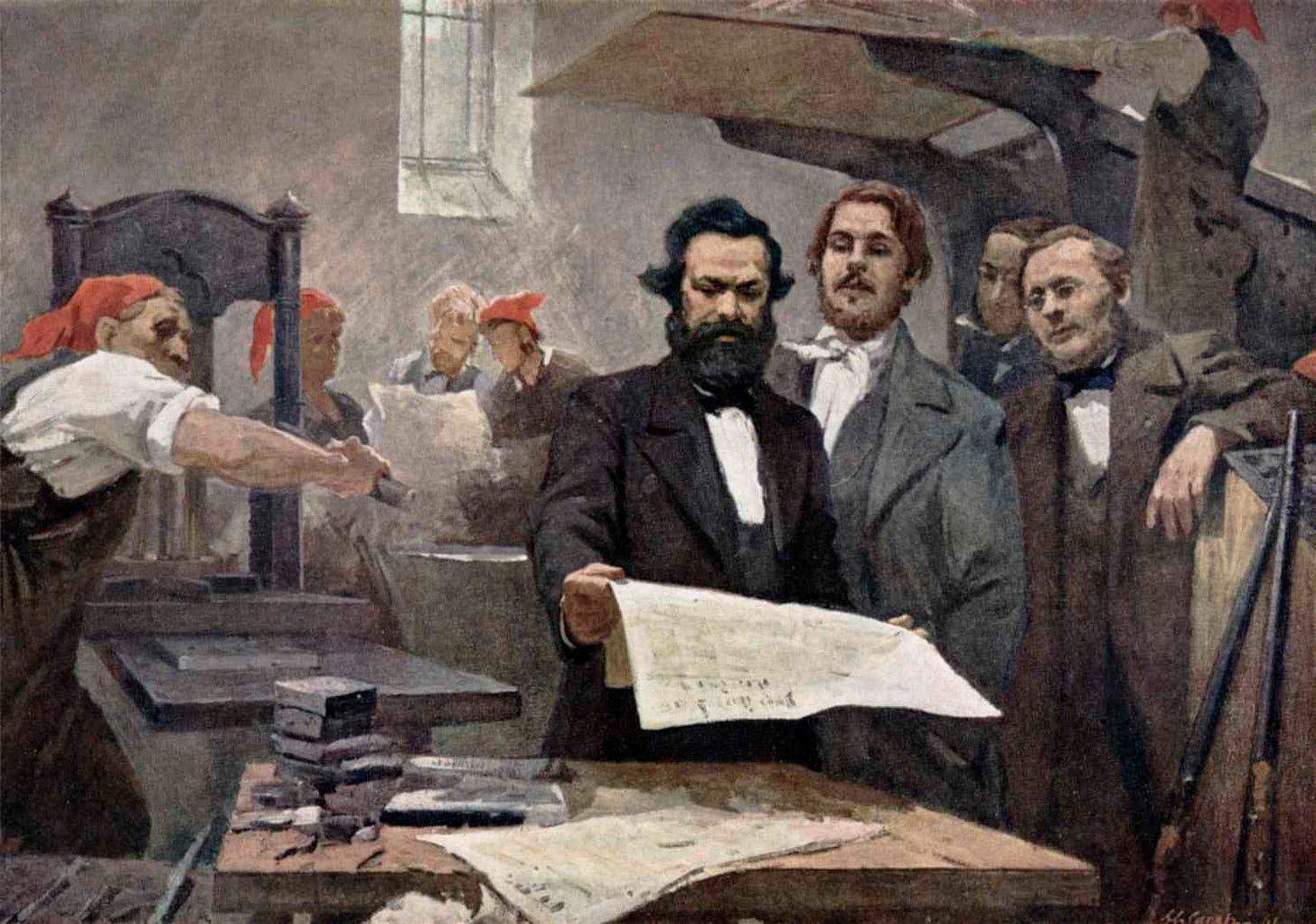

This argument finds at least indirect support in the Marxist tradition in an 1890 letter from Friedrich Engels to Joseph Bloch, in which Engels attempts to articulate the role of individuals in the production of history:

[H]istory forms itself in such a way that the ultimate result springs always from the conflicts of many individual wills, each of which in its turn is produced by a quantity of special conditions of life; there are thus innumerable forces which cross each other, an infinite group of parallelograms of forces, from which is derived one resultant—the historical event—which in its turn again can be considered as the product of an active power, as a whole unconsciously and involuntarily, because that which each individual wishes is prevented by every other, and that which results from it is a thing which no one has wished. In this way history runs its course like a natural process, and has substantially the same laws of motion. But, because of the fact that the individual wills—each of which wishes that to which it is impelled by its own physical constitution or exterior circumstances, i.e., in the last analysis, all economic circumstances (either its own personal circumstances or the general conditions of society)—do not reach that which they seek but are fused in one general media in a common resultant, by this fact one cannot conclude that they are equal to zero. On the contrary, each contributes to produce the resultant [my emphasis], and is contained in it.

In other words, even in a philosophical framework like Marxism, which is often characterized as socially deterministic, each one of us bears at least some responsibility in the production of the historical event. History is not the result of a the will of one individual or class but, instead, is produced through the complex interactions of multiple individuals and classes. The social contradictions that emerge from these interactions are, in this fundamental sense, our shared responsibility.

By way of contemporary example, we could use the argument from just deserts to make the case that liberals are wrong to advocate for the censorship of Trump supporters. This is because liberals themselves helped enable the conditions that led to the rise of Trump and his base in the first place, i.e. deindustrialization, forever wars, cultural elitism, etc. Not just “liberals,” in fact, but all members of American society, because we are all bound up—in one way or another—with the conflicts that have produced the current phenomenon of hyper-polarization in politics. To censor or cancel (and this goes the other direction, too) is to avoid the much more difficult task of reflecting on one’s own role (however small) in creating the conditions of possibility for “deplorable” views to gain traction in society in the first place.

The argument from just deserts could be strengthened by further clarifying how its moral conclusion can be drawn from its sociological premises. Indeed, one could reasonably object that it possible to both reflect and censor at the same time—that an understanding of the causes of objectionable views does not entail tolerance of those views in public discourse. In order to gain better traction, this justification for free speech would need to forge a stronger connection between the objective analysis of social life, on the one hand, and the subjective weight of individual ethical obligation, on the other.

#4: The Argument from Religious Humanism

All of the arguments so far grapple in one way or another with the question of the individual human being. This begs the question: Why does the individual matter in the first place? One answer to this question is provided by what I will call “religious humanism.” For religious humanism, the individual human being matters because he or she embodies an irreducible subjectivity and moral weight connected in some way to the sacred, spiritual, or divine.

In a formidable two-part essay published at Human Flourishing, philosopher Jens Zimmerman argues for the fundamentally Christian character of the religious humanist worldview:

God himself, in the person of Jesus Christ, showed human identity to be personal freedom lived in response to others, and so allowed individual freedom and difference to exist in communion bound together by love. I am not saying that Christianity single-handedly invented the concept of the person, nor were Christians consistently interested or successful in pursuing human dignity through their actions. At the same time, however, the concept of human persons would not have developed in the way I have described without the Christian message of God’s becoming human, suffering, and dying on the behalf of all, even for the “least of these,” in order to restore and perfect creation in the new humanity of Jesus Christ.

I take a less particularistic view and would suggest that the religious humanist conception of the human being has developed independently in multiple religious and philosophical lineages. From ideas of irreducible spiritual subjectivity in Islam to the moral significance of the only child in Buddhism, religious humanism has found expression in traditions outside the Christian fold. As such, I believe that an argument for free speech derived from a religious humanist framework could have appeal well beyond its clear historical resonance within Christianity.

A religious humanist argument for free speech takes as its foundation the conviction that every individual human being matters. This conviction implies that each individual’s voice matters; to censor those voices is an affront to the religious humanist conception of the human being. I have made a related argument previously on Handful of Earth in my essay on James Weldon Johnson’s hymn, “Lift Every Voice”:

To lift every voice means, necessarily, to accept the inherent unpredictability and, thus, potentiality, of each human individual. None of us knows what will transpire when every voice is lifted, but to fail to lift every voice would itself be a moral crime against the future, against another world that we cannot yet imagine without the assistance of every voice.

#5: The Argument from Duty

I concluded Part 1 of this essay with a turn toward a justification for free speech based in duties rather than rights:

Perhaps it will be an appeal to duty, rather than the liberal rhetoric of rights, that will reinvigorate the free speech movement in America today. In a world where we cannot put our trust in the “marketplace of ideas” to sort out truth from falsity, [we must be reminded] of the deeper meaning of free speech: the duty to pursue the truth and to act on the results of that pursuit in the face of repression.

I believe that the argument from duty is more important than ever in today’s world where it has become abundantly clear that classical liberal discourse on rights does not have the universal appeal that “end of history” theorists once assumed it did. The popularity of anti-liberal thinkers like Aleksandr Dugin in Russia, the growing influence of Iranian political theology in the Middle East, and the increasing popularity of Integralist Catholicism in the West are but a few examples of this trend.

The upshot is that there is no inevitable movement toward the mass adoption of classical liberal values. As a result, I believe that even classical liberal free speech advocates will need to be open to alternative justifications for free speech if they truly wish to see the value of free speech take root beyond the small global minority of diehard classical liberals. Arguments grounded in duty may hold the key to creating a sustainable culture of free speech.

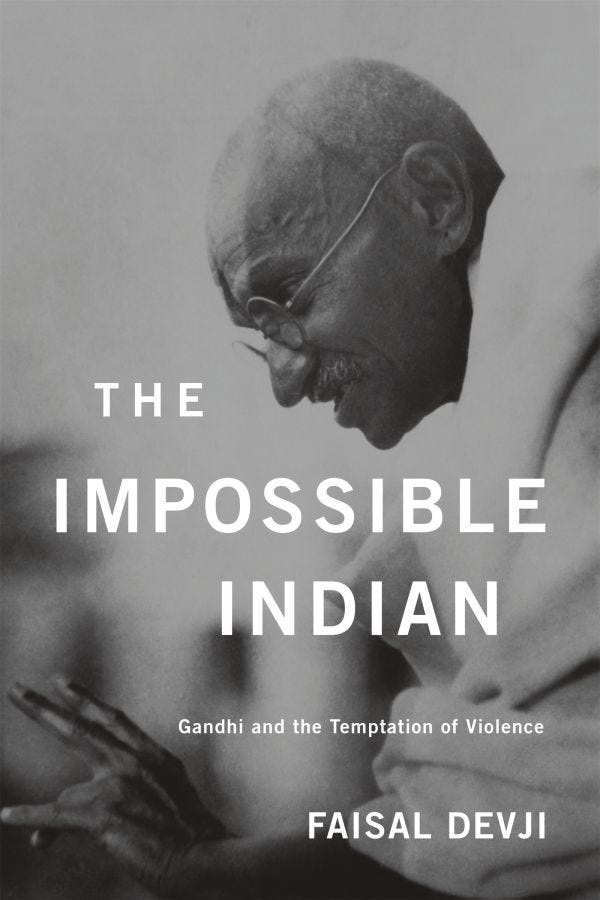

In his 2012 book, The Impossible Indian: Gandhi and the Temptation of Violence, historian Faisal Devji describes why Mahatma Gandhi privileged duties over rights:

[U]like rights, which can only be guaranteed by states and are thus never truly in the possession of those who bear them, duties belong to individuals and cannot be stripped from them. They represent in this sense the inalienable sovereignty of men and women, and therefore stand alone in their ability to create rights.

Gandhi’s duty supremacy, if you will, strikes a different chord from the classical liberal insistence on the right to free speech. An argument for free speech from duty is, perhaps paradoxically, more individualistic than an argument from rights. The rights-based approach relies on the existence of rights-bearing groups which can be transformed in a split second into rights-deprived groups by government decree. For free speech and other rights, it is the state that giveth and the state that taketh away.

The duty of free speech, in contrast with the right to free speech, is inalienable because it is possessed solely by the individual rather than granted to a collective by the state. This argument for free speech proposes that only from the wellspring of duty can the concept of a right to free speech be born, developed, and sustained. In other words, the duty of free speech is not opposed to the right to free speech; rather, it is the duty that makes the right possible.

The Urgency of Alternative Arguments for Free Speech

Why do arguments for free speech even matter? In Part 1 of this essay, I wrote that:

it is undeniable that American war-making abroad is one of the key drivers of resistance to classical liberal ideals—and the attraction of other ideologies—in the majority of the world. Unless classical liberals address this issue both ideologically and politically, their worldview will continue to fall flat among large swaths of the population.

I wrote these words before Hamas’ attack on Israel and Israel’s subsequent U.S.-backed war on Gaza. American support for the brutal Israeli regime—a supposed bastion of liberalism in the Middle East—has underlined why much of the world views classical liberal platitudes about free speech as hypocritical. These events have also ignited heated debates on the nature of liberal societies and the value of free speech in times of war, debates which I have participated in here at Handful of Earth. The overwhelming response in America to violence in the Middle East—a response of coordinated censorship and cancellation campaigns—demonstrates the urgency of alternative arguments for free speech.

Indeed, the fact that so many seemingly stalwart advocates of free speech could suddenly advocate for censorship at home in response to a new war abroad is testament to the weakness of the classical liberal argument for free speech, which has, in large part, lost its appeal in the face of an emotionally-charged conflict.

What we desperately need is an argument for free speech that can withstand the trials and tribulations of wars, pandemics, and other crises that are exploited to suppress freedom of speech. I hope that some of the alternative arguments outlined in this essay contribute to achieving this goal.