Monthly Muse: 9/2025

Recapitulation, contemplation, provocation

Monthly Musings are published during the last week of every month. In each Monthly Muse, I recap content from the past month of Handful of Earth, offer some freewheeling reflections, and share a passage that I’ve found especially thought-provoking.

Here’s the September 2025 Monthly Muse.

Recapitulation: Published since last month’s Monthly Muse

Contemplation

In this month’s article, “White-on-White Violence,” I argued that political violence in the United States is not only increasing, but is also increasingly internal to white America. A little over a week after writing this piece, I came across some remarkable data published by

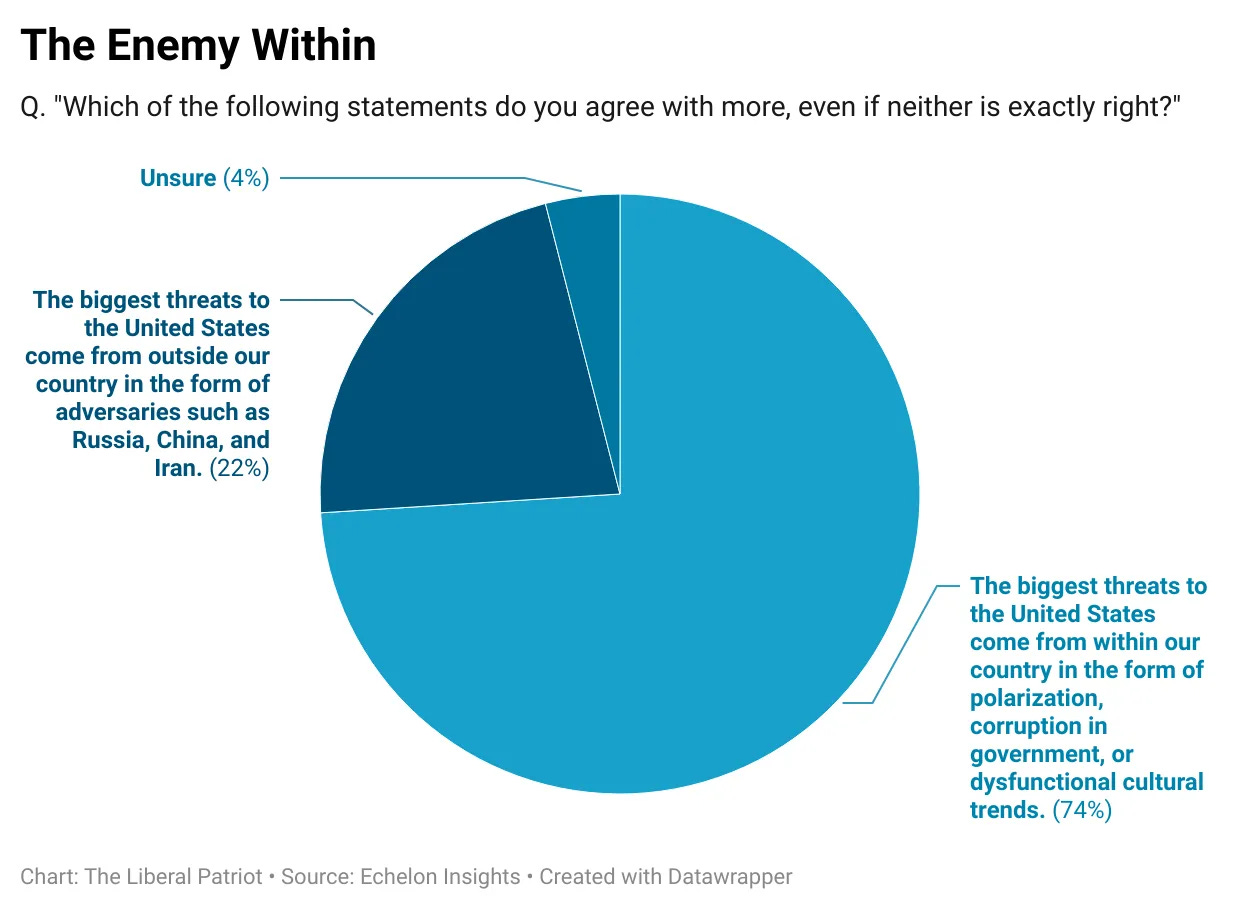

at The Liberal Patriot [TLP] in an article aptly titled “Americans Agree on One Thing—We Are Our Own Worst Enemy.”Halpin writes that “when TLP’s friends at Echelon Insights asked whether the biggest threats to the United States come from ‘outside our country in the form of adversaries such as Russia, China, and Iran’ or instead from ‘within our country in the form of polarization, corruption in government, or dysfunctional cultural trends,’ roughly three-quarters of American voters said our biggest threats are internal.”

The article notes that

Numbers this high almost always reflect basic consensus across demographic lines. Accordingly, around seven in ten Americans, regardless of their gender, age, education, race/ethnicity, or income, agree that our biggest threats are internal, not external. Similarly, in terms of partisanship, the difference is more a matter of degree rather than any serious disagreement about the location of threats to the nation: 63 percent of Republicans, 79 percent of independents, and 82 percent of Democrats believe our nation’s biggest threats are internal.

While Halpin’s piece doesn’t address the specific racial dynamics of increasingly explosive political divisions in the United States, his basic point that the vast majority of Americans consider internal threats to be more serious than external ones is significant.

This point seems all the more important to understand in a media climate that feeds on the presence of real or perceived external threats. With regard to Charlie Kirk’s assassination, serious questions have been raised about external actors. These are clearly important questions, but, for obvious reasons, we will likely never get answers about potential external involvement in the assassination. What we do know, however, is that the domestic political climate was already a tinderbox. With or without external influence, a small but growing number of Americans—especially white Americans—are prepared to die and even kill in the name of their ideological and political disputes with other Americans.

Halpin writes that “It’s easy for those who are partisan warriors or who are economically comfortable and successful to dismiss the concerns of Americans about internal threats as overblown, ‘fake news,’ or mass paranoia and neurosis. But this is a core part of the problem.” He returns to a fundamental question: “Can we really make it long-term with half the country hating the other half because of their political views?” For most Americans, Halpin states, “The answer right now is clearly no.”

Whether one favors the cohesion or the dissolution of the (strikingly old) American state, internal conflict is the fundamental problem in contemporary American politics.

Provocation

“The more I study the Civil War and Reconstruction, the more I am confirmed in the belief, derived from [W.E.B.] Du Bois, that together they represent a revolutionary upheaval as great as any. Not the English Revolution of the seventeenth century nor the French of the eighteenth involved such great masses of people nor such tremendous armies as the American Civil War; neither the Russian nor the Spanish Revolutions of the twentieth century took people from such a low state and hurled them so close to power as did the revolution that took ‘property’ and turned it overnight into soldiers, citizens, voters and officeholders. Only the Haitian Revolution of the eighteenth century and the Chinese of the twentieth compare with the American experience in breadth and depth, and in neither of those cases did the downtrodden come as close to power for as long as did American slaves after the Civil War.”

—Noel Ignatiev, “Whiteness and the Working Class”